Domestic violence or violence in intimate relationships

Domestic violence, or intimate partnership violence, is the most common type of gender-based violence.

According to the Istanbul Convention, domestic violence includes “acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence that occur within the family or domestic unit or between former or current spouses or partners, whether or not the perpetrator shares or has shared the same residence with the victim”.

Although the vast majority of domestic violence is perpetrated against women by men, it actually occurs in same sex relationships just as frequently as in heterosexual relationships, and there are cases of women abusing their male partners. Domestic violence such as rape, battering, sexual or psychological abuse leads to severe physical and mental suffering, injuries, and often death.

It is inflicted against the will of the victim, with the intention to humiliate, intimidate and exert control over her or him. Very often the victim is left without recourse to any remedies, because police and law enforcement mechanisms are often gender-insensitive, hostile or absent12.

A question often asked in relation to domestic violence is ‘why doesn’t (s)he leave?’ There is no simple answer to this question, because domestic violence is a complex phenomenon which often involves physical, psychological, emotional and economic forms of abuse. It may often lead to battered woman syndrome, where a woman in an abusive relationship starts feeling helpless, worthless, powerless, and accepting of the status quo. However, this syndrome does not explain why some women kill their violent partners and detracts attention from other reasons why women end up staying in a violent relationship. Such reasons may include financial dependence on the abuser, social constraints, and a lack of alternatives such as shelters for abuse victims. Domestic violence often involves isolation of the victim from family and friends, deprivation of personal possessions, manipulation of children, threats of reprisals against the individual, against children, or against other family members. Furthermore, common social pressures regarding the nature of a family – some kind of father is better than no father for your children – often makes getting out of an abusive relationship not only difficult, but also extremely dangerous.

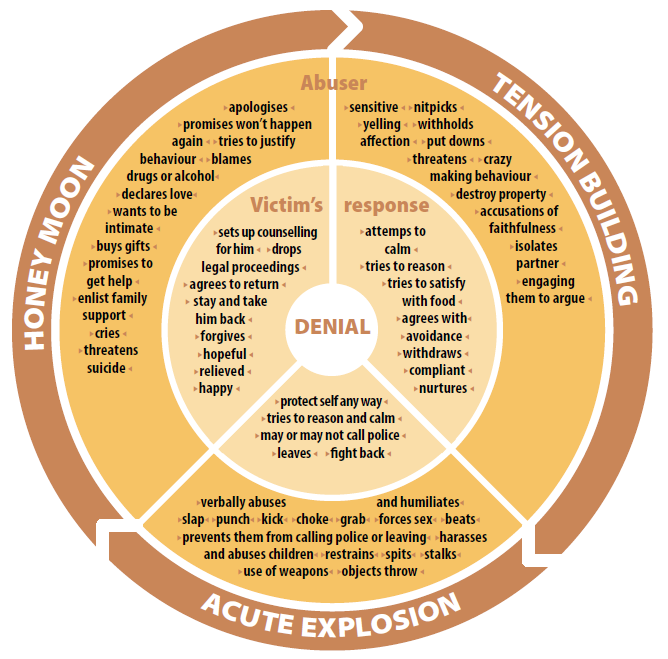

One further reason why people stay in abusive relationships can be understood through the so-called Cycle of Violence13:

The abusive behaviour involved in this cycle is sometimes instinctive and reactive, and sometimes planned and deliberate. It aims to keep the abused person in the relationship through promises and denials.

The basic cycle consists of an outburst of violence, which is followed by a so-called honeymoon period characterised by a sudden positive change in the behaviour of the abuser. It is known as the honeymoon period because victims often describe this period as being very similar to the early part of the relationship. The abuser is typically very apologetic about his or her behaviour, makes promises to change, and may even offer presents. However, this period does not last long, as its only function is to eliminate the worries of the victim regarding the future of the relationship. The victim is typically engaged and involved at this stage, as nobody likes to remember negative experiences. The victim therefore welcomes the apparent changes and promises made.

Once the victim’s worries have been silenced, the old power structure is reasserted. The many typical characteristics of domestic violence will again breed the kind of tension that eventually erupts in a further act of violence on the part of the abuser. Early in a relationship, violent incidents may be as far apart as six months or even a year, making it difficult to recognise the cyclical nature. Early incidents are likely to be verbal incidents followed by minor acts of physical violence, also making it hard for the victim to recognise the cycle, or to realise that put-downs, breaking of cups, even shoves and slaps are likely to escalate and end in beatings or worse.

The cycle does not only escalate as far as the severity of violence is concerned, but the incidents typically become closer to each other. Eventually, the honeymoon phase can disappear completely, and in some abusive relationships it may not exist at all. Instead, it may be replaced, particularly in social groups where domestic violence and rigid gender roles are less accepted, by attempts to minimise or deny the violence altogether.

In contexts where gender roles are more rigid, the perpetrator has greater freedom to deny responsibility. The set of gender roles that we are taught to adhere to as women and men contain many contradictions or demands that cannot be fulfilled. At the same time, part of the hegemonic male gender role is to oversee women and children in fulfilling their roles, and if necessary, to discipline them.

These two conditions combine to create common justifications for those who are abusive in relationships: they can easily find one thing or another to blame the woman for in cases of violence inflicted, and thereby to claim the right to inflict it.

In many countries, physical abuse and emotional abuse, often accompanied by acts of sexual violence, are seen as acts or crimes of passion, motivated by jealousy or the failure of the partner to fulfil expectations. Such a portrayal is particularly common in the media. However, this kind of vocabulary should be avoided when talking about forms of gender-based violence as it perpetuates ideas of impunity and implies responsibility on the part of the victim. The influence of alcohol is also often cited as a mitigating factor in cases of sexual abuse or exploitation, but this ignores the fact that abuse is perpetrated in a systematic way. As Ronda Copelon remarks, alcohol does cause violence, but “many men get drunk without beating their wives and… men often beat their wives without being drunk." To the extent that alcohol facilitates male violence, it is an important factor in the effort to reduce violence, but it is not the cause”14.

12 Copelon, R., (1994). ‘Understanding Domestic Violence as Torture’ in Cook, R. (Ed.). Human Rights of Women. National and International Perspectives. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. (p.116- 152)