Past Council of Europe Art Exhibitions

30th Art Exhibition "The Desire for Freedom. Art in Europe since 1945"

Berlin, Tallinn, Milan, Cracow, 2012-2014

29th Art Exhibition: The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation 962-1806

A two-part exhibition in Magdeburg (Cultural History Museum) and Berlin (German Historical Museum), 28 August-10 December 2006

When Austria’s Francis II stepped down as Holy Roman Emperor on 6 August 1806, an astonishingly long, unbroken line of rulers came to an end, and a unique political structure - the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation – disappeared with barely a whisper after more than 800 years. Transcending geographical, ethnic and religious boundaries, the Empire had covered much of Europe as we know it, taking in large parts of present-day Germany, Italy, France, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Austria and the Netherlands. Over the centuries, from Otto the Great to Francis himself, its destinies had been shaped by successive rulers, some dominating – others dominated by – the times they lived in.

To mark the 200th anniversary of the Empire’s dissolution, the Magdeburg Cultural History Museum and the Berlin German Historical Museum were staging a two-part exhibition, tracing its story from 962 to 1806, and running from 28 August to 10 December 2006. The first part, "From Otto the Great to the Close of the Middle Ages", was on show in Magdeburg, and was sponsored by the city and the Land of which it is capital, Sachsen-Anhalt. The second, "Old Empire and new states, 1495-1806", covering the later Empire, was mounted in Berlin. After the major medieval exhibitions devoted to Otto the Great (Magdeburg, 2001) and Henry II (Bamberg, 2002), this was the first to present a comprehensive picture of Germany’s and Europe’s development from the Middle Ages to the dawning of the modern era.

28th Art Exhibition: "Universal Leonardo"

Florence, London, Oxford, Munich and Milan in 2006

Universal Leonardo, an innovative Europe-wide project, was organised by the Universal Leonardo Bureau at Central Saint Martins College, University of the Arts in London, within the framework of the 28th Council of Europe Art Exhibition. It co-ordinated parallel exhibitions with the aim of broadening and deepening our understanding of Leonardo da Vinci’s contribution to art, science and technology.

The Universal Leonardo team worked with leading curators, art historians, academics and scientists throughout Europe to stimulate dialogue and discovery around Leonardo’s legacy, covering a broad range of topics in art and science, using, where appropriate, digital technology and innovative design.

27th Art Exhibition (Part 2) – The centre of Europe around 1000 A.D.

Budapest, Berlin, Mannheim, Prague, Bratislava, 2000 – 2002

The Centre of Europe around 1000 A.D. was a joint Czech, German, Hungarian, Polish and Slovakian exhibition project. It focused on the formation of central Europe, which began more than 1000 years ago with the entry of the West Slavs and Hungarians into western culture. Contact between these peoples and the neighbouring cultures - the Byzantine Empire to the south-east and the East Frankish, later Roman-German, Empire to the south-west - took many forms and varied in intensity.

Long-distance trade and raids, military occupation and royal legations, Christian missionary activity and pagan reaction, the politics of noble marriages, and contacts among ordinary country people all played a part. At the turn of the first millennium, the drive for integration into Latin-Christian culture laid the foundations for the attachment of the emerging Bohemian, Polish and Hungarian empires to the occidental world. When their rulers embraced Christianity, they founded Christian dynasties, which were to produce saints and patron saints such as Duke Wenceslas of Bohemia, Bishop Adalbertus of Prague and King Stephen of Hungary.

The exhibition, jointly prepared by all the countries involved was an academic affirmation of this spiritual and material tradition, illustrated through archaeological finds, written and pictorial evidence, objects of ritual and liturgical veneration and the evidence of political authority.

Thus "The Centre of Europe around 1000 A.D." was in itself a reflection of processes taking place in Europe today. The assembling of valuable objects and contemporary symbols of national identity in this context held up a mirror to present-day political developments.

27th Art Exhibition (Part 1) – Otto the Great, Magdeburg and Europe

Magdeburg, August - December 2001

The exhibition focused on three main themes: on the extraordinary ruler Emperor Otto 1 (936-973), already called "Otto the Great" by his contemporaries; on Magdeburg, one of his favourite places of residence and which, as an important trading place on the border between the Frankish Empire and the Slavs, achieved under Otto I great religious and political prominence; and lastly on the city’s special identity as a centre of culture and as a link between East and West. The exhibition highlighted the international dimension of the work of Otto the Great, reflected in his marriages to England’s Princess Edith and to Adelaide of Burgundy, the widow of Lothair, king of Italy, and the connection between the Ottonian Emperors and Byzantium, which was sealed in 972 by the marriage of Otto the Great’s son to the Byzantine princess Theophano.

The Magdeburg museum showed some four hundred works on loan from museums, libraries and archives throughout Europe and the United States. A combination of goldsmiths’ work, ivory carving, and illuminated manuscripts as well as textiles and sculptures gave a unique panorama of the age. Seals, official documents and archaeological findings rounded off the picture. With its wide variety of exhibits, the exhibition bore witness not only to an advanced civilization but also to aspects of everyday life in the 10th century.

26th Art Exhibition – War and peace in Europe

Münster and Osnabrück, October 1998 - January 1999

This exhibition marked the 350th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia which put an end to the Thirty Years’ War in 1648. By means of an outstanding collection of documents and works of art from the time, the exhibition presented the developments that led to this very destructive war in Europe, its ending thanks to the Peace Treaty and the subsequent effects it had. The aim was further to confront the beginnings of the modern age in the 17th century with the shape of Europe 350 years later in the last decade of the 20th century, both eras having been preceded by bloody conflicts and tremendous upheavals. In keeping with the historical events, the exhibition was twofold, with one part on display in Münster illustrating chiefly the artistic aspect and the other in Osnabrück on the historical context.

The Thirty Years' War was a time of misery, death and destruction brought about by dynastic and religious strife, power politics as well as longstanding conflicts. The European powers were involved in very different ways but the sporadic outbreaks of war and rebellion remained confined to given regions. It was not until the Bohemian uprising from 1618 to 1621 that sufficient explosive material was accumulated to hurl practically the whole of Europe into turmoil and destruction. Buildings, libraries, art-works and artists themselves came under constant threat; understandably the theme of war was greatly to influence art production at the time; but, as the exhibition demonstrated, the joy at the recovery of peace later found some of its greatest expressions in painting, music and literature.

25th Art Exhibition – Gods and heroes of the bronze age

Copenhagen, Bonn, Paris, Athens, 1998 – 1999

The exhibition was the crowning event of the "European Campaign for Archaeology", launched by the Council of Europe in 1994 and entitled "The first golden age of Europe". Both campaign and exhibition aimed to improve public knowledge and to illustrate the cultural relations between the peoples of Europe in the bronze age.

The exhibition opened up one of the most important eras of ancient Europe, roughly from 3 000 to 500 B.C., a time of change and renewal. Huge distances did not impede the emergence of a certain cultural unity in a region stretching from the Urals in the east to the Atlantic in the west and from what is now Scandinavia in the north to the Mediterranean in the south. To illustrate this, the exhibition put on show some of the most prestigious bronze age artefacts in Europe’s museums.

Gold artwork found in the tombs of Mycenae could be seen side by side with golden vases used as offerings in the the distant northern marshes and rivers. The famous Sun Chariot from Trundholm in Denmark was exhibited along with central European and Mediterranean ceremonial chariots; magnificent ancient armoury borne by Greek heroes could be seen next to the breastplates, swords, spears and shields of northern chieftains, as well as the mysterious “golden helmets” found in France and Germany, horned helmets and heavy ceremonial axes, and marvellous wind instruments: Danish lurs and Irish bronze horns. All these objects and many more, often remarkably beautiful, combined to produce a stunning vision of centuries of European history immortalized by Homer in the Iliad and the Odyssey.

24th Art Exhibition – The dream of happiness – the art of historicism in Europe

Vienna, September 1996 - January 1997

The late nineteenth century repeatedly used the trappings of the past to celebrate its own industrial might, disguising its factories and railway stations as castles and Renaissance palazzi, and even embellishing its machine tools with gothic ornament. Serenely proud of its economic and technical achievements, it looked back on twenty centuries of an idealised past, borrowing, amplifying and combining a whole range of stylistic elements to package its own glories.

Vienna, one of historicism’s main centres, made a perfect setting for the Council exhibition, which went beyond externals - the battle-scenes, princely processions and Pompeian palaces which throng the period’s paintings – to look at the reasons for this obsession with the past. The triumphant art of a bourgeoisie dazzled by its own success, historicism allied technical virtuosity with vivid artistic effects to celebrate the dawning of a new age. Not for everyone, however: the exhibition also went behind the ornate, classical facades to the sunless, overcrowded slums where the urban proletariat struggled to survive.

This was the grim reverse side of the often illusory "dream of happiness" which the historicists sought to sustain – and which also served to mask the gathering storm which burst over Europe in 1914. Hugely popular in the nineteenth century and decried by the modernists in the twentieth, historicism is now the focus of renewed interest by historians and public alike. Bringing together works from all parts of Europe, the Vienna exhibition offered a first overview of a movement which triumphed in a matter of decades, but has ever since been neglected by art-historians and scorned by critics.

23rd Art Exhibition – Art and power, Europe under the dictators 1930 – 45

London, Barcelona, Berlin, 1995 – 1996

At the 1937 Universal Exhibition, Vera Mukhina’s famous “The industrial worker and the collective farm girl” on the Soviet pavilion challenged the swastika-bearing eagle on the pavilion of the Third Reich right opposite, prefiguring the conflict between the two ideologies of fascism and communism. The Council of Europe exhibition, organised by the Hayward Gallery, examined the relationship between art and political power in Europe during the thirties and the war years when artists were faced with stark choices. It looked especially at the course of art and architecture in Spain, Mussolini's Italy, Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Soviet Union, and included art made in the service of the state as well as in opposition and exile.

The equestrian portraits of Mussolini or paintings of harvesters outstripping the objectives of the Plan are seldom considered key works of European art, but the exhibition showed how the regimes used art and artists to present an ideal world intolerant of contradiction or opposition. The art of the dictators, largely a combination of naive realism and hyperbolic classicism produced by some talented and some merely zealous artists, set the mighty power of the State against the fragility of the individual. So beyond simply presenting the works, the exhibition invited visitors to reflect upon the use of art as propaganda and how easy it is for political regimes to reactivate the mechanisms of self justification through art and culture. The show ended with a presentation of the work of so-called "bourgeois" or "degenerate" artists banned by these regimes simply because they refused to comply, thus underlining the prime importance of the freedom of art and expression for the freedom of society and democracy.

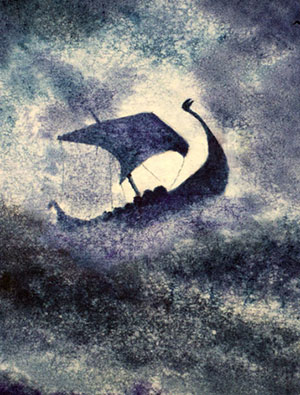

22nd Art Exhibition – From Viking to Crusader – Scandinavia and Europe 800 – 1200

Paris, Berlin, Copenhagen, 1992 – 1993

This, the first travelling exhibition organised by the Council, was also one of the most successful in the series, attracting over 700 000 visitors in the three cities where it was staged. Getting away from the stock image of savage marauders bent on pillage and destruction, it set out to portray an often misrepresented civilisation, which gave birth to Denmark, Norway and Sweden, but whose influence was felt well outside its home region.

Thanks to their impressive seafaring skills – the longship’s technical perfection still amazes – the Vikings won a footing in Ireland and England in the eighth century, colonised Iceland in 870 and Greenland a century later, and reached the coasts of Labrador in 982.

Contact with the Christian world led to their gradual conversion, and they played a major role in shaping medieval England and Russia. Jewellery, weapons, glassware, funeral ornaments and everyday objects helped to show how Viking society was organised and functioned, while displaying the Vikings’ skills and artistry. Bronze and gold, but also wood and bone, were their chosen materials, and the spiral, roundel and scroll their favoured forms. Outside contacts brought new influences – hence the imported Carolingian elements and the images of animals unknown in Scandinavia. Highlighting these aspects of their civilisation, the exhibition showed how the Vikings fused with the rest of Europe and left a lasting mark on it.

21st Art Exhibition – Emblems of liberty – the image of the Republic in Art

Bern, June - September 1991

Switzerland traces its origins to the oath of Rütli, sworn by the cantons of Schwyz, Uri and Nidwald, when they banded together in defence of their liberties in 1291. This, the country’s founding myth, served as starting point for the Berne exhibition, and centred on the ways in which republican liberties and values have been portrayed in European art and history.

From Venice to the United Provinces, the great republics of the past have left us group portraits of their Grand Councils and Assemblies – celebrating both their leading citizens and the institutions they directed. Frequently symbolised by female figures, republican values also find expression in architecture (think of town halls, the visible embodiment of local liberties). The exhibition’s second part focused specifically on Switzerland, charting the rise of its "canton republics", and particularly the city-state of Berne, most powerful of them all, which became the Republic of Berne in 1648. Eighteenth and nineteenth century paintings were included to illustrate the theme, "The Alps, cradle of liberty in Europe". Finally, the exhibition also looked at contemporary images of liberty in Europe and the world, at freedom of expression – and at ways of keeping those values alive.

20th Art Exhibition – The French Revolution and Europe

Paris, March - June 1989

Organised as part of the celebrations to mark the Revolution’s bicentenary, the Council exhibition provided a sweeping panorama of the ten, world-shaking years from the fall of the Bastille to Napoleon’s seizure of power as First Consul.

The first section was devoted to France and Europe in the run-up to 1789. The second used documents and pictures to chart the course of the Revolution itself, with a special emphasis on "revolutionary propaganda" – the drawings, caricatures and images of emblematic events, such as the National Assembly’s abolition of feudalism and the execution of Louis XVI, which helped to spread the message at home and abroad. The third was concerned with the "creative revolution" and the iconography of its great ideas – with liberty, equality, fraternity, the rights of man, and the ways in which symbols, such as "trees of liberty" and the "cult of reason", were used to project them.

The revolutionary governments had their cultural policies as well, setting up museums to promote their ideology and supporting artists who served it. The exhibition covered these lesser-known aspects of the Revolution thoroughly, including works by "great names", like David and Houdon, and also artists now totally forgotten. Like the Revolution, it ended with Napoleon. Without seeking to pass judgment on a tumultuous, controversial epoch, when many things went right and as many went wrong, it used objects and images to convey a vivid sense of the age and its ideas – helping to fill in the background to the year-long bicentenary celebrations.

19th Art Exhibition – Christian IV and Europe

Denmark (10 venues), March - September 1988

Christian IV, who ruled Denmark from 1588 to 1648, may not have been totally successful as a monarch (territorial losses at the end of his reign marked the first stage in the decline of Danish power), but he remains a mythical figure - remembered above all for his passionate interest in architecture and the arts.

The royal palaces and museums of Copenhagen, and also Frederiksborg Palace – a "Nordic Renaissance" masterpiece built by Christian between 1600 and 1620 - housed the Council exhibition, covering art and civilisation during his reign. Uniquely, and thanks to loans from many countries, Christian’s collection of art–works, partly broken up and carried off in the wars which followed his death, were brought together for the exhibition, complementing the Rosenborg Treasure, which comprises the Danish royal collections and such items as Christian’s crown and regalia. The originals of Adrian de Vries’s famous bronze sculptures, conceived for the fountain at Frederiksborg and taken as booty to Sweden in 1659, were among the most spectacular pieces on show.

Alongside the furniture, tapestries, arms and works of art which reflected the Danish court’s splendour, the exhibition covered the intellectual and scientific life of the epoch, tracing Denmark’s relations with the rest of the world, and focusing on the navy and seafaring, the army, the daily life of the people and Christian’s image in history to give an all-round picture of a reign which marked the apogee of Denmark’s "golden century".

18th Art Exhibition – Anatolian civilisations

Istanbul, May - October 1983

The first urban settlements in Anatolia date back some 9000 years and already prefigure the region’s later bridge function between East and West. Spread through the sumptuous palaces and museums of Istanbul, the Council exhibition traced the civilisations which succeeded one another as the millennia passed, from paleolithic and neolithic all the way to the Ottomans.

The art and culture of the Hittites (2000 – 1200 B.C.) reflected their contacts with the Babylonian civilisations on the Tigris and Euphrates; in the fourth century B.C., this eastern strain coloured and enriched the classicism of the Greek kingdoms, and it reappeared under the Roman Empire, when the Province of Asia (the westernmost part of Anatolia) served as the conduit. Under Byzantine rule for seven centuries, Anatolia was converted to Islam by the Seljuks in the eleventh century. Next came the Mongols, followed by the Ottomans, who remained in power from 1299 to 1923, when the present Republic of Turkey was founded.

Drawn from all over Turkey and many other parts of Europe, the archaeological and artistic treasures on show in Istanbul bore witness to this rich, incessant commingling of civilisations. Focused on the main periods of Anatolian history, the exhibition also followed a number of thematic strands. One of these was the lifestyle of the region’s nomad communities; far from being purely ornamental, the forms and colours of their tents reflect the owners’ social standing and function.

17th Art Exhibition – Portuguese discoveries and Renaissance Europe

Lisbon, Spring – Summer 1983

By 1500, the great voyages of discovery initiated by Portugal’s seafarers in the mid-fifteenth century had made Lisbon the capital of an empire stretching from the Indies to Brazil, and had played a major part in giving Europe a window on the rest of the world. Bearing witness to this age of wealth and growth, the great buildings constructed under Manuel I (1495-1521) housed this massive historical exhibition, covering art, science, technology and ideas. Its ship-building and map-making skills, and above all the astrolabe which enabled its ships to steer by the stars, were the instruments of Portugal’s expansion.

The story was told in the exhibition’s main section, for which the Jerónimos Monastery – a masterpiece of Manueline architecture, blending late Gothic and oriental influences – provided a sumptuous setting. From botany to zoology, all the sciences gained from the great voyages of discovery, while a new sense of the world’s immensity and contacts with unknown peoples did much to shake Europe’s old certainties. All of this is reflected in the exotic beasts and landscapes featured in the Portuguese art of the time, which absorbs these elements and the influence of other European countries without losing its own character. The exhibition also included an extensive display of weapons (in the Belem Tower) and traced the history of the Aviz dynasty, which dominated this great period, when Portugal was one of the world’s leading maritime powers.

16th Art Exhibition – Florence and Tuscany under the Medici

Florence, March - June 1980

Even when economic and political decline set in as the sixteenth century unfolded, Florence still retained its intellectual and artistic dominance. Housed in the city’s finest palazzi, the Council exhibition traced the city’s contribution to European culture and surveyed the fruits of its influence. While emphasising painting and sculpture, represented by artists like Bronzino, Pontormo, del Sarto and Cellini, the exhibition reflected the intellectual ferment of the Renaissance, which saw the rise of science and technology – but also had time for alchemy and the occult.

It showed how the court of the Medici became a model of magnificence and refinement, and contrasted the dynasty’s image with that of other ruling families in Europe. Without equalling the splendour of his fifteenth-century forebears, Cosimo the Younger restored the power of the state and finished beautifying the city. Taking "space and power" as one of its themes, the exhibition looked at the image of the Tuscan state embodied in its architecture and went on to consider "architecture and the representation of monarchy" more broadly in France, Spain, England and the Empire. By looking beyond Florence and its treasures, and making these international comparisons, it vividly conveyed the city’s huge and lasting influence on the rest of Europe.

15th Art Exhibition – Trends in the 1920s

Berlin, August - October 1977

In the 1920s, the Weimar Republic was a seething hotbed of artistic creativity, and Berlin the place where all the avant-garde trends converged. Indeed, "Berlin in the twenties" has acquired mythic status, and its short-lived role as the cradle and focus of modernity was celebrated in the Council exhibition, which covered all the great movements of the time in painting, architecture and the decorative arts from the birth of abstraction to surrealism. From the forms and colours of Malevich, Kandinsky and Mondrian, through Dix’s apocalyptic visions to the jarring mockery of the Dadaists, it captured the stormy, pulsing vigour of a time when all the old landmarks and conventions were overturned and swept away.

While the Bauhaus, founded in Weimar by Gropius in 1919, was pioneering functionalism in architecture and the decorative arts, Garnier and Perret were devising an aesthetic to fit the industrial cities of the future. This was one aspect of the exhibition. Another was surrealism, strongly represented by Chirico, Mirò and Magritte. The exhibition also filled in the political and cultural background, showing how relations between art and society were changing, and highlighting, in particular, the immense impact on the arts of the Russian Revolution.

14th Art Exhibition – The Age of Neo-Classicism

London, September - November 1972

After the swirling excesses of baroque and rococo, the neo-classical style gave Europe and its cities a dose of Greek severity between 1780 and 1830. Rectilinear and rational, neo-classicism sought inspiration in the treasures of classical antiquity, which the archaeologists had been busily unearthing since the 1750s. Turn-of-the-century London became a second Athens, with museums and banks as its temples, and the same rigorous hellenism ran through Europe from Munich to Copenhagen. The Romans found admirers too, and the Empire style in France helped to make a conscious link between Napoleon and Augustus.

While artists like David and Canova took the style into painting and sculpture, neo-classicism found its fullest expression in architecture – hence the special importance attached in the exhibition to such master-architects as Nash, Soane, Schinkel, Klenze and Brongniart. The popularity of "classical" furniture may have been short-lived, but neo-classical buildings did much to change the face of Europe’s cities, and remain the enduring legacy of an artistic movement which faded out slowly and stayed influential through much of the nineteenth century. Finally, the exhibition highlighted the role of leading theorists and writers, such as Goethe and Winckelmann, in forging the neo-classical aesthetic.

13th Art Exhibition – The order of St John in Malta

Valletta, April - July 1970

The Order of the Knights of St John, founded in Jerusalem in the twelfth century, came to Malta in 1523. With the passing of time, it took on many of the trappings of statehood, with Valletta as its proud capital. Under the aegis of its Grand Masters, its membership included the fine flower of Europe’s nobility. Its original purpose was to care for the poor and the sick, but it soon acquired a maritime and economic power which lasted until Napoleon extinguished it bloodlessly on his way to Egypt in 1798.

The French were soon ousted, however, and Malta passed under British rule until 1964. Spread between the finest palaces in the fortified town, the Valletta exhibition set out to convey the pride and grandeur of the Order and its knights, who employed some of the best artists of their time. One of these was the Italian, Mattia Preti (1613-98), who painted the sumptuous baroque frescoes in the Cathedral and decorated many other churches. His pictures, on loan from collections in Malta and many other parts of Europe, and works by Caravaggio and Antoine de Favray were the finest paintings in the exhibition, which also included portraits of the Grand Masters and knights who ruled the island. Coins, plans, models, books and pictures served to illustrate the Order’s history, and the exhibition also took in the famous Hospital of the Knights – symbol of one of their enduring functions.

12th Art Exhibition – Gothic Art

Paris, April – July 1968

The pointed arch and ribbed vault – these were the hallmarks of the revolutionary new style which took hold in the Ile-de-France around 1130 and went on to dominate European architecture and art for the next three centuries, giving our continent many of its greatest masterpieces.

Ever bolder in conception, soaring cathedral spires came to symbolise the Gothic spirit, while sculpture shook off the inertia of past centuries and developed a new feeling for movement and space. Stained glass, chiefly used to fill open spaces in arches and bays, reached a level of perfection never rivalled since, while the cathedrals became repositories of objects d’art made of gold and precious stones. Bridging the gap between the exhibitions devoted to Romanesque and fifteenth-century art, the Paris show brought together sculptures, paintings, goldsmith’s work and manuscripts from some fifteen countries, making it easier to trace national and regional variations on the basic style and themes of Gothic. Another of its aims was to highlight the ways in which art and belief connected – to show that religious faith guided the stone-mason’s chisel and mallet

11th Art Exhibition – Queen Christina of Sweden

Stockholm, June - October 1966

Earlier Council exhibitions had focused on major periods in the history of European art, but Aachen and Stockholm broke new ground by turning the spotlight on important historical figures and using them to illuminate an epoch. Thus the Stockholm show, although centred on Christina, also provided a broader view of seventeenth-century Sweden and its relations with the outside world.

Born in 1626, Christina became queen in 1650, abdicated in 1654, converted to Catholicism and spent most of the rest of her life in Rome, where she died in 1689.

The exhibition traced the career of this remarkable woman, who was one of the leading minds of her time – and also one of its most dedicated art-collectors. Against the background of Stockholm and Sweden’s development, and of the economic, intellectual and cultural life of the country, the exhibition followed Christina to Rome and on her many other journeys. In her Roman palazzo, surrounded by artists and intellectuals, she amassed paintings, engravings, drawings and medallions, many of which went into the exhibition’s "artistic" section. As a patron of letters and the arts, she looked ahead to the Enlightenment. Politically, her role in Swedish history was minor, but her intellectual distinction lent lustre to her century – and looking at her life can help us to see that century in a new and unexpected light.

10th Art Exhibition – Charlemagne – His life and work

Aachen, June - September 1965

Charlemagne, the first great architect of European unity, was crowned Emperor on Christmas Day in the year 800. The exhibition in Aachen (his capital, where he lived from 794 to his death in 814) centred both on the art of his era, and on perceptions of Charlemagne himself – the myth which grew up around him in the middle ages and is still potent today. In a society to which he brought peace and stability, the "Carolingian Renaissance" found expression, first of all, in the rule of law - itself reflected in the many codices and charters assembled for the exhibition.

The profound Christianity of Emperor and Empire appear in the reliquaries and gospels lent by museums and abbeys the length and breadth of Europe, and in the rich ivory bindings sent from Ravenna. Charlemagne’s enduring charisma is reflected in the gem-studded, gold and silver bust-reliquary, crafted 500 years after his death, and in his silver sceptre set with agates, his gold and silver sword, his horn, his knife and his shoes – relics half-real, half-legendary, and the focus of a cult repeatedly reburnished as the centuries passed. From Dürer’s portrait of 1512, through tapestries to illuminated books, his image is a constant in European art and historiography – often a blend of fantasy and fact, but always evoking a short-lived golden era when the concept of Europe took shape for the first time.

9th Exhibition – Byzantine art

Athens, April - June 1964

The Roman Empire in the West collapsed in the mid-fifth century, but the Christian Empire in the East survived for a thousand years after that, disappearing only when Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453. Covering that period and its art, the Athens exhibition brought out the profound originality of the Byzantine world-view, with its synthesis of Hellenistic and Christian values – a blend reflected in the Empire’s mosaics, frescoes and paintings, as well as its architecture and sculpture. Richly ornate, Byzantine art is both profoundly human and deeply religious.

Huge though the Empire was and long as it lasted, its art retained a basic unity – just as its architecture evolved within set stylistic and technical norms. The mosaics and icons which instantly evoke Byzantine art naturally dominated the exhibition, but jewellery, ivories, textiles, manuscripts and goldsmith’s work were featured too. The exhibition also made it clear that Byzantine influence extended well beyond the Empire’s frontiers, and remained a living force throughout Europe, long after Constantinople had fallen.

8th Art Exhibition – European art around 1400

Vienna, May - July 1962

In spite of undoubted masterpieces, the arts of the late middle ages have often been seen as a kind of prelude to the Renaissance, and their own special features and worth disregarded. The exhibition organised at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum helped to lift the curtain on this neglected era – and illustrate the intense cultural exchange typical of Europe around 1400. This was the age when the Gothic style reached its apogee in Europe, transcending frontiers and winning acceptance in cities as far apart as Paris and Cologne, Dijon and Prague.

Sumptuous and sophisticated, "international Gothic" was ideally suited to the great courts of Europe, to the Dukes of Burgundy in Dijon and the Habsburgs in Prague. The "courtly style", with its rich decoration and subtle colours, was adopted by tapestry–weavers and goldsmiths too. It infused sculpture and painting with a new sensibility and contributed to the rise of drawing and wood engraving. The main works on display were Burgundian and Austrian, and the exhibition also featured seals, coins, illuminated manuscripts and glass paintings, all drawn from the Viennese museums’ rich holdings, with numerous pieces from Italy to broaden the perspective.

7th Art Exhibition – Romanesque art

Barcelona and Santiago de Compostela, July – October 1961

Around the year 1000, Romanesque architecture emerged as Christian Europe’s first great unifying style, reaching its high-point in cathedrals, churches and abbeys. Organised simultaneously in Barcelona and Santiago de Compostela, the exhibition brought together over 2000 exhibits from the Iberian peninsula and from the regions traversed by pilgrims on their way to Compostela – Western Europe’s greatest pilgrimage. It set out to show the ways in which Romanesque art diverged from the “classical” style inherited from the Roman Empire, and to point up variations between countries.

Spain was one of its most fruitful centres, giving it a language of its own – in contrast to outlying areas, beyond the Roman Empire’s reach, where Romanesque influence blended with surviving traditional styles, Celtic or Scandinavian, for instance.

Some of the finest examples of Romanesque art are to be found in the doorways and tympana of churches, and in the fantastic beasts and demons which decorate their sculpted capitals. Combining biblical episodes with scenes from daily life, Romanesque statuary offers us a vivid chronicle of three centuries of Europe’s human and spiritual history.

6th Art Exhibition – Sources of the 20th century: the arts in Europe 1884 – 1914

Paris, November 1960 – January 1961

In the period running from the creation of the Paris Salon des Indépendants in 1884 to the outbreak of war in 1914, Europe witnessed an unprecedented explosion of new artistic styles, all paving the way towards twentieth-century modernism. In France, the Nabis, the Fauves and the Cubists revolutionised line and colour, casting off representational constraints and striking out in wholly new directions. In centres like Paris, Brussels, Vienna and Glasgow, architecture and the decorative arts also broke new ground, shaking off the academicism of preceding decades.

From Braque to Franz Marc, from Loos to Mackintosh (not forgetting the one-off originals, like Van Gogh or Rousseau), the Council exhibition provided a first, panoramic survey of turn-of-the-century modernism – and so constituted an important art-historical event in itself. It also traced the new relations which developed between society, art and artists, showing how official institutions rejected most of the new painters, while the new styles in architecture and the decorative arts – e.g. the "modern style" and Art Nouveau – were more readily accepted for both public buildings and private houses.

5th Art Exhibition – The romantic movement

London, July – September 1959

London’s Tate Gallery, home to Turner’s best-known pictures, provided a perfect setting for the Council’s exhibition on romanticism – England itself being a major centre of that tumultuous movement which swept over Europe in the first half of the nineteenth century. Turner’s jagged rocks and stormy seas, Friedrich’s isolated figures and landscape immensities, and the hectic drama of Géricault and Delacroix all speak of an age when feelings and passions ran unchecked, and individuals and peoples alike aspired to new freedoms.

But the London exhibition was also concerned to show where Romanticism came from and what it led to, and even to highlight the work of artists who – like Constable, with his tranquil scenes of country life – stood aside from the movement.

This was a time when painting and literature were closely allied, and romantic literature also featured prominently, reminding visitors that many of the movement’s leading figures were at once painters, writers, sculptors and draughtsmen. Combining new emotions with the rapturous rediscovery of an idealised, medieval past, Romanticism developed a fierce, primal energy, which swept our nineteenth-century forebears on towards modernism.

4th Art Exhibition – The age of rococo

Munich, June - September 1958

The fourth Council exhibition went well beyond its title to embrace the full range of eighteenth-century art, of which rococo proper was only one aspect. Rococo itself, that exuberant, luminous blend of late baroque and Enlightenment sophistication, is seen at its best in the palaces and churches of southern Germany, but also in its decorative arts, furniture, metalwork and china, all of them well represented among the 900 items on show.

The spirit of the movement, and its delight in clarity and asymmetry, are reflected in the work of its painters: in Boucher’s voluptuous and Fragonard’s coy visions of female beauty, in the fountains and waterfalls which animate their landscapes, in Canaletto’s and Tiepolo’s celebrations of the Venetian Republic’s fading glories, and in Gainsborough’s portrait evocations of the new society then emerging in London. From Messerschmidt’s "character heads" to Piranesi’s "Prisons", the arts of sculpture and engraving also received broad coverage.

Finally, numerous books served to underline the vital role of publishers in the Enlightenment, while also showing how the arts of the era found expression in book illustrations and bindings.

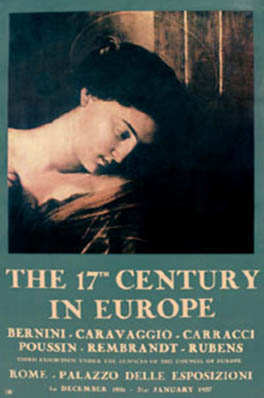

3rd Art Exhibition – The 17th century in Europe – realism, classicism and baroque

Rome, December 1956 - January 1957

Rome, cradle of the baroque style from the early 1600s on, retained its influence as one of the great centres of European art throughout the seventeenth century, attracting artists from all parts of the continent. The flowering of baroque doubtless left its deepest mark on architecture, first in Rome and later throughout all Italy, Spain, Portugal and the Habsburg countries, but the Council exhibition focused on painting, offering visitors a chance to compare trends which, although contemporary, seemed at first sight to have little in common.

Caravaggio and the Carraccis dominated the Italian scene, where baroque and realistic elements existed side-by-side, while Poussin, La Tour and Le Nain pioneered the new styles, from classicism through baroque to realism, in France. Baroque and Counter-Reformation may have been the main trends in seventeenth-century Europe, but neither is particularly evident in the “burgher” portraits of Frans Hals and the young Rembrandt, or the genre and maritime scenes which express the self-assurance of Holland’s “golden century”. Chosen from all over Europe, the works on display certainly reflected the divisions of the age, but they also – beyond the two extremes, baroque and classical – offered glimpses of an area where the influences blended, and seemingly incompatible styles came together to express the spirit of a century where light and shade ruled by turns.

2nd Art Exhibition – The triumph of mannerism from Michelangelo to el Greco

Amsterdam, July - October 1955

Originating in Italy around 1520 and spreading throughout Europe in the course of the next century, the mannerist style took over the Renaissance heritage and “manner”, deliberately exaggerating it in an effort to do better, at the risk of seeming affected or grotesque, and not always with happy results. Striking but tortured, sumptuous but agitated, mannerism triumphed in Tuscan and Venetian painting, came to France with the School of Fontainebleau, and eventually spread as far north as Scandinavia.

Although works by Michelangelo, Tintoretto and El Greco were among its highlights, the Council exhibition did not stop at painting, but went on to show how architecture, sculpture and the decorative arts all surrendered to the new style. Intricate examples of the goldsmith’s art, a profusion of carved ivories and metal wrought into gold and silver-gilt flowers – often the work of south German and Austrian craftsmen – bore splendid witness to an art essentially conceived for princes and frequently at odds with the troubled second half of the sixteenth century. Tapestries, furniture, weapons, armour and coins completed this vast, panoramic survey of a style often belittled in the past – but which the exhibition helped visitors to see with new eyes.

1st Art Exhibition – Humanist Europe

Brussels, December 1954 – February 1955

It is not at all surprising that the very first exhibition in the Council of Europe series was devoted to Humanism: a notion traditionally associated with Europe more than with any other civilization. Centred on man, beauty and knowledge, and finding inspiration in the rediscovered masterworks of classical antiquity, the humanist philosophy of the mid-fifteenth century helped to bridge the gap between the late middle ages and the Renaissance. Brussels, one of the new movement’s centres, played host to this art exhibition – a show redolent of the shared values on which Europe was then being rebuilt.

Erasmus of Rotterdam and his three celebrated portraitists, Metsys, Dürer and Holbein, were emblematic of an exhibition which brought together the likenesses and works of the scholars and artists who made up a universal "Republic of Letters", taking in such varied figures as Leonardo Da Vinci, Van Eyck, Paracelsus and Thomas More. Alongside the paintings and engravings, the printing press which served to disseminate the new learning had pride of place in the display: in addition to Gutenberg’s 36- and 42-line Bibles, a host of books printed in Flanders and along the Rhine gave a vivid sense of the growth of knowledge, the movement of ideas and people, and the new importance attached to education.