Remembrance

What is Remembrance?

Remembrance: noun

- Memory or recollection in relation to a particular thing

- The action of remembering

- A memorial or record of some fact, person etc.

Oxford English Dictionary

Gross human rights violations, atrocities such as the Holocaust, slave trade, genocide, wars and ethnic cleansing, have been part of European history throughout the centuries. Remembrance is the act of honouring the memories of the victims and survivors of such events, of the resistance fighters, as well as the commitment to never repeat such atrocities.

When hearing the word remembrance, most people tend to think about commemorative events organised around a national or international day of significance. But remembrance can take many shapes and forms and it becomes even more meaningful when organised in interdisciplinary approaches. Remembrance actions, which can range from formal and non-formal educational activities to marking sites, building memorial and museums, conducting research and writing books, organising guided tours and cultural events, as well as passing legislation to protect the survivors or to condemn denial, distortion or trivialisation of such events.

Governments of many countries around the world did not want or still do not want to assume responsibility for their past actions. But official recognition of such events is important not only for the people who were affected by them, but for the society as a whole. Society needs to "remember" its own history – including those events which have disrupted the lives of many – in order to learn from the past and build better societies in the present. Remembrance, when done properly, can serve as a warning signal to society: it can show us how human action or inaction, bigotry, racism, intolerance, antisemitism and other relatively common attitudes can lead, under certain circumstances, to events which are truly terrible.

Forgetting is not easy, even if you want to forget.

Mr. Bayijahe, survivor of the Rwanda genocide

The information in this section covers issues relating to the question of what societies should do to remember – collectively – terrible events when mass human rights violations have occurred.

Question: Which events are officially remembered in your country?

Remembrance and human rights

That's the problem with the exceptional. The exceptional becomes the normal and then it becomes too little and then you have to make it more exceptional and more exceptional and more exceptional. And the dagger aimed at the enemy in the end is plunged inwards, perforating the very character of your own society and rupturing precisely what it is supposed to defend.

Justice Albie Sachs

There is no human right directly connected to the act of remembrance, but the type of events which society feels the need to remember are often those where the human rights of certain groups of individuals have been comprehensively ignored. We remember the Holocaust because Jews, as well as Roma, disabled people, homosexuals, Jehova's witnesses, people of particular political beliefs, and certain Slavic people were treated as lesser human beings and experienced violations of almost every one of their human rights. We remember wars, primarily because there are times when death visits both civilians and those involved in the fighting on a mass scale. We remember deportations or instances of ethnic cleansing not just for the fact that the victims experienced systematic violations of their human rights, but also because the violations were directed at these particular groups, and for no other reason than that the groups were viewed as sub-human, as people unworthy of the full range of human rights. We remember genocides because these are occasions when the elimination of a whole people is undertaken deliberately. The intention to eliminate an entire group of people, the development of a systematic process of elimination, the planning and the atrocious acts committed strike at the most basic human rights principle: that all people should be regarded as equal in dignity and rights.

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

Article I: The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.

Article II: In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Which human rights?

The modern framework of human rights was developed in the aftermath of WWII and the atrocities committed in the war and during the Holocaust were viewed as important aspects to address in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In commemorative events the number of people who were murdered is often mentioned, but the right to live was only one of the many rights that were violated in those instances. Genocides, do not happen overnight, they start with discrimination and progressive human rights violations. Wars are depicted as having a “winning” side and a “losing” side, but clearly, people on all sides have been seen by “the enemy” as being of less value. If we understood that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights, we would make more efforts to use peace-building efforts or negotiation rather than turning to warfare.

The Holocaust is regarded as a paradigm for every kind of human rights violation and crime against humanity; all victims are taken into consideration.

Council of Europe1

When the infrastructure of a country is destroyed, or when the number of refugees escaping ethnic cleansing overwhelms the services of their new host country, the "victims" of the original action multiply. New methods of warfare leave behind unexploded ordinance which kills or mutilates, leave chemical debris which causes ill-health, and leave a broken infrastructure which cannot provide for the basic needs of those who may have survived.

If we do not acknowledge the "slower" victims of terrible events and we cannot obtain an accurate picture of the total number who may have suffered, how then can we assess the consequences of such actions? How can we "remember" them accurately, and how can we learn from them for the future?

Agent Orange

Agent Orange was a defoliator widely used in the Vietnam War. Its effects on the environment and on people linger on today. An estimated 4.8 million Vietnamese people were exposed to Agent Orange, resulting in 400,000 people being killed or maimed, and 500,000 children being born with birth defects. In 2010, victims were still seeking justice and compensation from courts in the United States of America.

Question: Which victims of the Second World War are "counted" in your country? Can you think of others whose lives were cut short but do not feature in the official count?

Forgetting human rights

This sin will haunt humanity to the end of time. It does haunt me. And I want it to be so.

Jan Karski, who took the message about the Polish Ghetto to the wartime Allies, and was disbelieved.

When terrible events are given "official" status as something society should never forget, survivors or people who were affected by the events can have some comfort that society has acknowledged that the action was wrong. They can also have some hope that they are no longer regarded as a group of people whose rights can be disregarded. Sadly, many peoples around the world do not receive even this small comfort: the number of terrible events which societies do not remember far outnumber those which we acknowledge and commemorate.

There are some events that are remembered, but which we do not necessarily recall or know about in any detail or are we able to connect them with our present societies:

- How much do we really know about the terrible details of the slave trade, the numbers killed and the appalling conditions in which slaves were deported and made to work? How many people are aware of the fact that the Roma were slaves in Romania for 500 years?

- Across Europe, we commemorate the Second World War and the Holocaust, but how many people understand how the Holocaust was possible in a relatively civilised Europe or know the level of involvement and responsibilities of the other countries, besides Germany? How many people know more than a few dates, a few numbers (not always correct) and Auschwitz? Are we aware that Jews were systematically persecuted or murdered, but that other groups were also perpetrated and killed?

- How much do we recognise the role that our own country played in the Second World War – whichever side it fought on? Wars are terrible times and it sometimes seems that any means are justified to bring war to an end, or beat the enemy. Yet there are standards even during times of war, and the mass bombings of German towns, where hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed, almost certainly violated these standards.

- How do we perceive the crimes of Stalinism, including massive deportations and famine? Who should remember them today?

- What do we do about the remembrance of the Genocide of Armenians and other Christians during the final years of the Ottoman Empire?

- How much do we really care to know about the effects of colonialism in African countries, for example Congo or Algeria? How much do we prefer not to know?

Question: How many of the events listed below have you heard about? Can you think of other similar types of atrocities which your own country was involved in?

Our future is greater than our past.

Ben Okri

There are other events which are barely remembered at all, even by countries which played a part in causing them – and even when past suffering has continued to play a role in violations of rights experienced to this day:

- In 1966 Nigeria suffered a civil war and attempts were made to completely rid Nigeria of Biafrans. Every means possible was used to exterminate and cleanse the country of all traces of Igbo and Easterners. The U.K., Russians, East Germans and Egyptians also participated in what led to the killing and torture of millions of Biafran people.2

- The population of North America before Columbus' arrival in 1492 is estimated at between 1.8 million and 12 million. Over the following four hundred years, their numbers were reduced to about 237,000. Many Native Americans were directly murdered by European colonisers; others died from diseases which were introduced by the colonisers.

We only become what we are by the radical and deep-seated refusal of that which others have made of us.

Jean-Paul Sartre

"…European Christian invaders systematically murdered additional Aboriginal people,

from the Canadian Arctic to South America. They used warfare, death marches, forced

relocation to barren lands, destruction of their main food supply – the Buffalo – and

poisoning. Some Europeans actually shot at Indians for target practice."3

- In 1885, the Congo became part of Belgium, by decree of Prince Leopold. Vast supplies of rubber helped to make the king one of the wealthiest people in the world. But in some areas, up to 90% of the population were wiped out because they interfered with attempts to satisfy increasing demand for rubber.

"Villagers were flogged publicly, burnt to death and their hands were cut off if they

didn't produce enough rubber. Soldiers were ordered to cut off the hands of all those

they killed as proof that they did not waste the ammunition they had been given. In

fact every soldier was supposed to produce a right hand for every shot fired."4

- In 1944, almost the entire Chechen population was deported over a few days, in the middle of winter, on a journey lasting 2 or 3 weeks. They were loaded into cattle trucks and only allowed to take 3 days' worth of rations. Between a third and a half of the entire nation are thought to have died either on the road or afterwards in exile. Other ethnic groups from the Caucasus also suffered deportation on a mass scale, as did Poles, Volga Germans, people from the Baltic States and the Crimean Tartars.

Deportation of Chechen people

European Parliament recommendation to the Council on EU-Russia relations

[The European Parliament] Believes that the deportation of the entire Chechen people to Central Asia on 23 February 1944 on the orders of Stalin constitutes an act of genocide within the meaning of the Fourth Hague Convention of 1907 and the Convention for the Prevention and Repression of the Crime of Genocide adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 19485

Protecting human rights through remembrance

All who have taken seriously the admonition "Never Again" must ask ourselves – as we observe the horrors around us in the world – if we have used that phrase as a beginning or as an end to our moral concern.

Harold Zinn, historian

The connection between remembrance and human rights ought to extend both backwards and forwards in time. Terrible events which have been brought about through human action or inaction deserve to be remembered partly as a sign of respect to the victims who perished or otherwise suffered in the past. Yet the forward-looking aspect of remembrance is equally important, and much more often neglected, particularly when it involves the need to recognise our own role in causing terrible events.

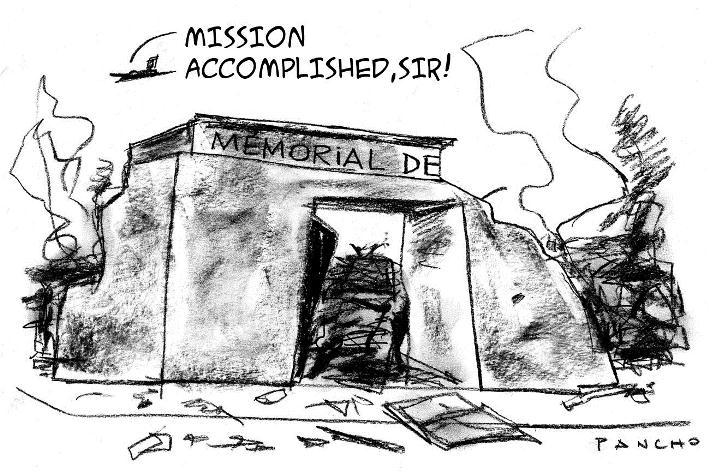

Official remembrance is normally organised by governments, and governments are not always prepared to admit to past mistakes or to having undertaken actions which have had severe consequences in terms of human rights. Countries tend to remember their own victories and their own victims, but they very rarely acknowledge the victims of other countries. A US General made the famous statement at the start of the Afghanistan conflict that "we don't do body counts". He meant that we do not count the Afghan victims of the war, but of course every country "counts" their own victims, whether military or civilian. How many of the countries currently involved in the conflict in Afghanistan have tried to keep a record of civilian casualties in that country, let alone of all casualties?

If remembrance is to help us avert future mass violations of human rights, we need to be honest about looking at ourselves! We need to be aware of the consequences of official policies in our country which may bring about violations of human rights in other countries. We need to acknowledge mistakes we may have made in the past and notice those we may be committing now. Only then can we begin to learn from them.

Question: Do any of the official remembrance events or memorials in your country recall mistakes or crimes committed by your own government?

Restoring justice

Unable to forget

The fascists destroyed our lives, so that even today we are unable to forget. Today we wander through the whole of Europe, searching for what the fascists took from us. Among us there are children who have Romani mothers and German fathers – children whose mothers were raped and came into the world that way, children like J.S. and A. who wander with us as Roma and not as Germans. They also are seeking a place where they can stay and lead meaningful, dignified lives.

Sefedin Jonuz

It's very hard to build a democracy that respects the rule of law when people who have committed mass crimes are not punished and are allowed to walk around the streets.

Human Rights Watch

The Holocaust, together with the Second World War itself, is probably the best "remembered" event throughout Europe. Yet the Roma, who were one of the most targeted and victimised groups, are still a people who suffers terrible discrimination throughout Europe. In the past few years, in numerous Council of Europe states, we have seen violations of Roma rights, which have been condemned by international human rights bodies. Clearly, our methods of "remembering" the Holocaust – and learning from it – seem to have been inadequate.

There are generally believed to be four essential elements in restoring justice to victims of terrible crimes:

1. Acknowledge the crime

2. Condemn the actions which led to it

3. Compensate the survivors

4. Remember what happened, so that the actions are not repeated.

Acknowledge

The sacrifice they commemorated was entirely male and military. The cemeteries were not designed as places to remember the sacrifices of women, children, refugees or animals. Their design commemorated death, but not the other perspectives of the combatants' lives – fear, filth, boredom – nor humour, camaraderie, or resignation.

Sonia Batten

Acknowledging what has happened helps people – individuals and countries – come to terms with the past and helps them to move on socially, politically and economically. An acknowledgment might be a formal apology by a state. In South Africa after the Apartheid era, in Morocco, Chile and Argentina, and in the former Yugoslavia the process of acknowledging responsibility for the atrocities has been greatly helped by truth and reconciliation processes.

Injustices cannot be remedied if they are not acknowledged. The suffering of Roma people has barely been acknowledged. If it was, perhaps governments across Europe might take stronger measures to assist a people whose memories are still raw; and perhaps they would do more to stamp out continuing discrimination against them.

Condemn

When crimes are committed, there is a need for a full investigation, and for those responsible to be condemned and brought to trial. Since the setting up of the International Criminal Court – and the possibility that crimes of genocide can now be heard – there is a chance that mass human rights violations can be considered properly, and condemnation can follow. However, it is important that the Court is seen to be thoroughly objective, and that it does not fall into the errors committed by the Nuremberg Trial, seen by many as engaging in "victor's justice". Proper condemnation should consider the role of all parties to any conflict or any act of genocide – whether or not it seems clear to outsiders that one party was primarily to blame.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was criticised by many for not considering the NATO bombing campaign, despite evidence from Amnesty International and other human rights organisations that war crimes had been committed by both sides.

Question: Should those who claim to be acting to protect human rights be condemned if they also violate human rights?

Compensate

Since the Second World War, Germany has enacted a number of laws providing compensation for people who suffered persecution at the hands of the Nazis. In 1951 Konrad Adenauer, the Federal Republic of Germany's first Chancellor, stated: "In our name, unspeakable crimes have been committed and demand compensation and restitution, both moral and material, for the persons and properties of the Jews who have been so seriously harmed…" However, it was only in 1979 that Nazi persecution of the Roma was identified as being racially motivated. Although they then became eligible to apply for compensation for their suffering, many had already died.

Many other examples abound, such as the women who were raped during wars in former Yugoslavia and who have not received any compensation for this.

Remember

Even once an event has become worthy of official remembrance – and victims have been acknowledged as genuine victims – the way that remembrance is organised, and the messages put out to society, can fail to identify the "correct" lessons to be learned. If we had really been successful in remembering slavery and other crimes of the colonial era, would countries which committed these crimes not have made sure that their people were fully aware of the extent of suffering caused? If official memories of the Second World War had been honest, would we not also acknowledge the war crimes committed by the Allied forces? And if we had been successful in remembering the Holocaust, would we not have recognised the suffering of the disabled, homosexuals and the Roma? Yet these three groups continue to be some of the most discriminated against across the whole of Europe.

Question: What are, in your opinion, the lessons we should learn from the Holocaust?

Certainly, when we learn about the suffering, persecution, discrimination and human rights violations of a group of people we should be able to understand that something like that should never happen to those people, but also that something like that should not happen to anyone. Unfortunately, this extrapolation is often missed by people who study history. Human rights can become an important catalyst in making this connection and in understanding the equality in human dignity inherent to all of us.

Without acknowledgement, condemnation, compensation and remembrance, it is likely that the memory of injustice and mass human rights violations will be used to justify actions. The manipulation of collective memories for the purpose of national political agendas remains a serious threat across Europe. The polemics raised in Spain about restoring dignity to the victims of the Spanish civil war, and the tensions between and within Armenia and Turkey about the enforced mass displacement, with the ensuing deaths as well as the outright killings of ethnic Armenians in 1915 under the Ottoman Empire, are only two examples of the risk of using memory for creating further dissention and conflict.

Oral History

Oral history methodology focuses on people as the agents of history and uses memory as a means of making sense of the past in the present. By putting together personal memories and stories from various sides in conflict, oral history focuses on people while promoting multiple perspectives in history and supporting reconciliation. Remember for the Future is a project of DVV International (German Adult Education Association) that uses oral history to support reconciliation and dialogue; the project has focused on South Eastern Europe, but has evolved to other regions and partners, including Armenia and Turkey and the Russian Federation.6

The Council of Europe's work

Education

We want the memorials to be centres for the exchange of ideas, not collections of bones.

Ildephonse Karengera, Director of Memory and Prevention of Genocide in Rwanda

The Council of Europe, which emerged from the ruins of the Second World War, has defined its fundamental objectives with a view to countering the totalitarian ideologies that dominated the first half of the 20th century and their corollaries: intolerance, separation, exclusion, hatred and discrimination. The values which the Council of Europe stands for – democracy, human rights and the rule of law – are part of a preventive post-war effort which guarantees the construction of a European society striving to learn to respect the equal dignity of all, thanks to, among other things, intercultural dialogue.

Since 1954, the European Cultural Convention has highlighted the importance of teaching the history of all the member States in its European dimension, in order to foster mutual understanding and to prevent such crimes against humanity happening again. It was in the framework of the Learning and Teaching about the History of Europe in the 20th Century project in schools that the Holocaust theme found its place.

In 2001, the Council of Europe introduced a Day of Remembrance of the Holocaust and for the Prevention of Crimes against Humanity, with the aim of developing and firmly establishing the teaching of this subject throughout Europe. There is not one specific date for the European Day of Remembrance. Each member state should choose a date that corresponds with its national history and in this way ensure that pupils are aware that it is their own cultural heritage which is being referred to.

Historical controversies should not hold human rights hostage. One-sided interpretations or distortions of historical events should not be allowed to lead to discrimination of minorities, xenophobia or renewal of conflict. New generations should not be blamed for what some of their forefathers did.

Thomas Hammarberg, Council of Europe Human Rights Commissioner

The Parliamentary Assembly has regularly called for multi-perspectivity in history teaching. In its recommendation 1880 (2009), the assembly reaffirmed that "history also has a key political role to play in today's Europe. It can contribute to greater understanding, tolerance and confidence between individuals and between the peoples of Europe or it can become a force for division, violence and intolerance". History teaching can be a tool to support peace and reconciliation in conflict and post-conflict areas. The recommendation stresses that there can be many views and interpretations of the same historical events and that there is validity in a multi-perspective approach that assists and encourages students to respect diversity and cultural difference, instead of conventional history teaching, which "can reinforce the more negative aspects of nationalism".

Shared Histories for a Europe Without Dividing Lines is a history project that is being implemented with historians, curriculum designers, textbook authors, writers of other pedagogical materials and history teacher trainers. The project seeks to highlight the common historical heritage of peoples in Europe through better knowledge of historical interactions and convergences, with the aims of conflict prevention and gathering support for reconciliation processes.

… everything possible should be done in the educational sphere to prevent recurrence or denial of the devastating events that have marked this century, namely the Holocaust, genocides and other crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing and the massive violations of human rights and of the fundamental values to which the Council of Europe is particularly committed.

Council of Europe Committee of Ministers7

The Council of Europe sees the passing on of the remembrance of the Holocaust and the prevention of crimes against humanity as going hand-in-hand with promoting its fundamental values and intercultural dialogue. Proposals for actions include special events, the training of executives of youth movements, youth associations and specialised NGOs and giving particular attention to combating Holocaust denial and revisionism. This will take place through ad hoc training for teachers dealing with the attitudes of vulnerable teenagers in search of their identity and likely to be influenced by exclusion demagoguery or fascinated by the horrors of the Holocaust. At the same time thought will have to be given to the use of the new means of communication used especially by youth, for networking and for passing on the message through "multipliers".

Youth

Remembrance is relevant for young people. Apart from involvement in armed conflicts – as perpetrators or targets of human rights violations – young people are the primary target of remembrance activities and projects because it is through them that reconciliation and dialogue should be exerted. Many international youth organisations have therefore been created in order to overcome hatred and prejudice; international solidarity is thus meant to replace nationalist and xenophobic views on the world. The creation of the Franco-German Youth Office in 1963 is an example of the commitment to reconciliation and the role young people play in it. The office was set up by France and Germany to promote dialogue and exchange between French and German youth, but nowadays it also involves other countries.

Question: Do you think you have any responsibility with regards to your country’s past?

A people without memory are in danger of losing their soul.

Ngugi wa Thiong'o

Youth organisations are traditionally active, directly and indirectly, in remembrance activities with young people. Organisations representing young people belonging to minorities in Europe are carriers of memory and identity of these communities Consequently they have both a direct educational function for their members and a role as representatives of the minorities within the wider society. Other youth organisations are active in informing and raising awareness about major human rights violations and in promoting reconciliation and dialogue. Both the European Youth Centre and the European Youth Foundation actively support such activities. These include awareness and learning from and about the Holocaust, the Armenian and Rwandan genocides, co-operation and peace building across different communities and engaging in dialogue with the "other sides" in conflict, such as in the Youth Peace Camp. The European Union of Jewish Students, in co-operation with other organisations, has initiated a series of educational activities on genocide by putting together the work on Holocaust with other genocides, including those in Rwanda and in Darfur.

Break them with the pressure of propaganda or break them with torture. Don't allow them to die; don't allow them to deteriorate to the point where it's no longer possible to question them. Interrogator's Manual, Cambodia

The Roma Youth Action Plan foresees an important dimension of strengthening Roma youth identity; this includes knowledge about Roma history and language, both within and outside Roma communities, such as activities on International Roma Day and Roma and Sinti Genocide Remembrance Day.

Endnotes

1 www.coe.int/t/dg4/education/remembrance/archives/dayRemem_en.asp

2 http://ositaebiem.hubpages.com/hub/BIAFRA-THE-FORGOTTEN-GENOCIDE

3 www.religioustolerance.org/genocide5.htm

4 http://globalblackhistory.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/forgotten-history-king-leopold-and.html

5 European Parliament, (2003/2230(INI))

6 www.historyproject.dvv-international.org

7 Recommendation Rec(2001)15 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on history teaching in twenty-first-century Europe

Key Date

- 27 JanuaryInternational Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust

- 8 MarchInternational Women’s Day

- 21 MarchInternational Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

- 7 AprilDay of Remembrance of the Victims of the Rwanda Genocide

- 1 MayInternational Workers Day

- 5 MayEurope Day

- 8-9 MayTime of Remembrance and Reconciliation for Those Who Lost Their Lives during the Second World War

- 21 MayWorld Day for Cultural Diversity for Dialogue and Development

- 26 JuneUnited Nations International Day in Support of Victims of Torture

- 18 JulyNelson Mandela International Day

- 2 AugustInternational Remembrance Day of the Roma Holocaust, the Porrajmos

- 6 AugustHiroshima Day

- 9 AugustInternational Day of the World’s Indigenous People

- 23 AugustInternational Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition

- 23 AugustEuropean Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism

- 21 SeptemberInternational Day of Peace

- 9 NovemberInternational Day Against Fascism and Antisemitism

- 29 NovemberInternational Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

- 2 DecemberInternational Day for the Abolition of Slavery

Memory is what shapes us. Memory is what teaches us. We must understand that's where our redemption is.

Estelle Laughlin, Holocaust Survivor