Legal protection of human rights

We already know that human rights are inalienable rights possessed by every human being, but how can we access these rights? Where can we find evidence that these rights have been formally recognised by states? And how are these rights implemented?

Domestic Human Rights

It goes without saying that human rights protections and understandings are ultimately most reliant on developments and mechanisms at the national level. The laws, policies, procedures and mechanisms in place at the national level are key for the enjoyment of human rights in each country. It is therefore crucial that human rights are part of the national constitutional and legal systems, that justice professionals are trained about applying human rights standards, and that human rights violations are condemned and sanctioned. National standards have a more direct impact and national procedures are more accessible than those at the regional and international levels. As Eleanor Roosevelt observed:

Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any map of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person: the neighborhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere.2

The duty of the State to respect, promote, protect and fulfil rights is therefore primary, and that of regional or international tribunals subsidiary, coming into play mainly where the state is deliberately or consistently violating rights. We all know examples of how resort to regional and international mechanisms has become necessary for the acknowledgement that violations are occurring at the national level. Regional and international concern or assistance may be the trigger for securing rights domestically, but that is only done when all domestic avenues have been utilised and exhausted. It is for this reason that we dedicate the rest of this section to exactly this scenario. What resort is there where domestic systems have failed to ensure adequate protection for the enjoyment of human rights?

Question: Why do you think that even states with a very poor record on human rights are ready to sign international human rights treaties?

Human rights are recognised by agreements

Every soul is a hostage to its own actions.

The Koran

At the international level, states have come together to draw up certain agreements on the subject of human rights. These agreements establish objective standards of behaviour for states, imposing on them certain duties towards individuals. They can be of two kinds: legally binding or non-binding.

A binding document, often called a Treaty, Convention or Covenant, represents a voluntary commitment by states to implement human rights at the national level. States individually commit to being bound by these standards through ratification or accession (simply signing the document does not make it binding, although it represents the willingness to facilitate this). States can make reservations or declarations in line with the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which exempt them from certain provisions in the document, the idea being to get as many of them as possible to sign. After all, it is better to have a state promising to comply with some human rights provisions than with none! This mechanism, however, can sometimes be abused and used as a pretext for denying basic human rights, allowing a state to "escape" international scrutiny in certain areas.

Human rights have, however, also permeated binding law at the national level. International human rights norms have inspired states to enshrine such standards into national constitutions and other legislation. These may also provide avenues for redress for human rights violations at the national level.

By contrast, a non-binding instrument is basically just a declaration or political agreement by states to the effect that all attempts will be made to meet a set of rights but without any legal obligation to do so. This usually means, in practice, that there are no official (or legal) implementation mechanisms although there may be strong political commitments to have them.

Question: What is the value in a mere "promise" to abide by human rights standards, when this is not backed up by legal mechanisms? Is it better than nothing?

The law does not change the heart, but it does restrain the heartless.

Martin Luther King

Meetings of the United Nations General Assembly or UN conferences held on specific issues often result in a United Nations declaration or non-binding document also referred to as "soft law". All states, simply by being members of the United Nations or by taking part in the conference, are considered to be in agreement with the declaration issued. The recognition of human rights should also, at the national level, be the result of an agreement between a state and its people. When human rights are recognised at the national level, they become primarily a political commitment of a state towards its people.

Key international documents

The importance of human rights is increasingly being acknowledged through wider instruments offering such protection. This should be seen as a victory not only for human rights activists, but for people in general. A corollary of such success is the development of a large and complex body of human rights texts (instruments) and implementation procedures.

Human rights instruments are usually classified under three main categories: the geographical scope (regional or universal), the category of rights provided for and, where relevant, the specific category of persons or groups to whom protection is given.

At the UN level alone, there are more than a hundred human rights related documents, and if we add in those at different regional levels, the number increases further. We cannot consider all these instruments here, so this section will only deal with those that are most relevant for the purpose of human rights education in Compass:

- documents which have been widely accepted and have laid the ground for the development of other human rights instruments, most particularly the International Bill of Rights. (For more specific instruments, such as the Refugee Convention, Genocide Convention and instruments addressing International Humanitarian Law, please refer to the thematic sections of Chapter 5.)

- documents relating to specific issues or beneficiaries, which are explored in this manual

- the major European documents.

United Nations Instruments

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is the most important of all human rights instruments.

The most important global human rights instrument is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948 by the General Assembly of the UN. This is so widely accepted that its initial non-binding character has altered, and much of it is now frequently referred to as legally binding on the basis of customary international law. It is the touchstone human rights instrument from which tens of other international and regional instruments, and hundreds of domestic constitutions and other legislation, has drawn inspiration.

The UDHR consists of a preface and 30 articles setting forth the human rights and fundamental freedoms to which all men and women everywhere in the world are entitled, without any discrimination. It encompasses both civil and political rights as well as social, economic and cultural rights:

- Right to Equality

- Freedom from Discrimination

- Right to Life, Liberty, Personal Security

- Freedom from Slavery

- Freedom from Torture and Degrading Treatment

- Right to Recognition as a Person before the Law

- Right to Equality before the Law

- Right to Remedy by Competent Tribunal

- Freedom from Arbitrary Arrest and Exile

- Right to Fair Public Hearing

- Right to be Considered Innocent until Proven Guilty

- Freedom from Interference with Privacy, Family, Home and Correspondence

- Right to Free Movement in and out of the Country

- Right to Asylum in other Countries from Persecution

- Right to a Nationality and the Freedom to Change it

- Right to Marriage and Family

- Right to Own Property

- Freedom of Belief and Religion

- Freedom of Opinion and Information

- Right of Peaceful Assembly and Association

- Right to Participate in Government and in Free Elections

- Right to Social Security

- Right to Desirable Work and to Join Trade Unions

- Right to Rest and Leisure

- Right to Adequate Living Standard

- Right to Education

- Right to Participate in the Cultural Life of Community

- Right to a Social Order that Articulates the UDHR

The Declaration also contains a strong reference to community and citizenship duties as essential to free and full development and to respecting the rights and freedoms of others. Similarly, the rights in the declaration cannot be invoked by people or states in violating human rights.

International Bill of Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) both came into force in 1976 and are the main legally binding instruments of worldwide application. The two Covenants were drafted in order to expand on the rights outlined in the UDHR, and to give them legal force (within a treaty). Together with the UDHR and their respective Optional Protocols, they form the International Bill of Rights. Each of them, as their names indicate, provides for a different category of rights although they also share concerns, for example in relation to non-discrimination. Both instruments have been widely ratified, with the ICCPR having 166 ratifications and the ICESCR 160 ratifications, as of November 2010.

Further to the International Bill of Rights, the UN has adopted a further seven treaties addressing particular rights or beneficiaries. There has been mobilisation for the idea of particular rights or beneficiaries – for example child rights for children – as despite the application of all human rights to children and young people, children are not seen to enjoy equal access to those general rights and they are in need of specific additional protections.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) recognises that children have human rights too, and that people under the age of 18 need special protection in order to ensure that their full development, their survival, and their best interests are respected.

The International Convention on the Elimination All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965) prohibits and condemns racial discrimination and requires states parties to take steps to bring it to an end by all appropriate means, whether this is carried out by public authorities or others.

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW, 1979) focuses on the discrimination which is often systemically and routinely suffered by women through "distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women […] of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil, or any other field". (Article 1) States undertake to condemn such discrimination and take immediate steps to ensure equality.

The Convention Against Torture and Other Forms of Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (1984) defines torture as "severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental" (Article 1.1), which is intentionally inflicted in order to obtain information, as punishment or coercion or based on discrimination. This treaty requires states parties to take effective measures to prevent torture within their jurisdiction and forbids them from returning people to their home country if there is reason to believe they would be tortured there.

The Convention on the Protection of the Rights of Migrant Workers and members of their Families (1990) refers to a person who "is to be engaged, is engaged or has been engaged in a remunerated activity in a State of which he or she is not a national" (Article 2.1), and to members of his/her family. As well as delineating the general human rights which such people should benefit from, the treaty clarifies that whether documented and in a regular and legal situation or not, discrimination should not be suffered in relation to the enjoyment of rights such as liberty and security, protection against violence or deprivation of liberty.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities marks a groundbreaking shift not only in its definition of people with disabilities but also in their recognition as equal subjects with full and equal human rights and fundamental freedoms. The treaty clarifies the application of rights to such people and obliges states parties to make reasonable accommodation for people with disabilities in order to allow them to exercise their rights effectively, for example in order to ensure their access to services and cultural life.

The Convention on Enforced Disappearances addresses a phenomenon which has been a global problem. The treaty prohibits the "arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty" (Article 2), whether by state agents or others acting with the states' acquiescence followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person. It states that no exceptional circumstances whatsoever for this refusal to acknowledge deprivation of liberty and the concealment of the fate and whereabouts of victims. Its objective is to end this cynical ploy and attempt to inflict serious human rights violations and get away with it.

|

Major United Nations’ Human Rights Treaties |

||

| Treaty | Monitored by | Optional Protocols |

| International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (1965) |

Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination | |

| International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) | Human Rights Committee | First Optional Protocol establishing an individual complaint mechanism Second Optional Protocol aiming at the abolition of the death penalty |

| International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966) |

Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights | Optional Protocol recognising the Committee’s competence to receive communications submitted by individuals or groups (2008) |

| Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) | Committee on the Rights of the Child | Optional Protocol on the involvement of children in Armed Conflict (2000). Optional Protocol on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (2000). Optional Protocol allowing children to bring complaints directly to the Committee (2011). |

| Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979) | Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women | Optional Protocol on the right to individual complaints |

| Convention Against Torture and Other Forms of Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (1984) | Committee against Torture | Optional Protocol establishing a system of regular visits by independent international and national bodies - monitored by the Subcommittee on Prevention (2002) |

| Convention on the Protection of the Rights of Migrant Workers and members of their Families (1990) | Committee on the Protection of the Rights of Migrant Workers and members of their Families | |

| The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) | Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities | Optional Protocol on Communications allows individuals and groups to petition the Committee. |

| The Convention on Enforced Disappearances (2006) | Committee on Enforced Disappearances | |

Protection of specific groups at the UN and European levels

As well as recognising the fundamental rights of individuals, some human rights instruments recognise the rights of specific groups. These special protections are in place because of previous cases of discrimination against groups and because of the disadvantaged and vulnerable position that some groups occupy in society. The special protection does not provide new human rights as such but rather seeks to ensure that the human rights of the UDHR are effectively accessible to everyone. It is therefore incorrect to pretend that people from minorities have more rights than people from majorities; if there are special rights for minorities, it is simply to guarantee them equality of opportunities in accessing civil, political, social, economic or cultural rights. Examples of groups that have received special protection are:

Minorities

States shall protect the existence and the national or ethnic, cultural, religious and linguistic identity of minorities within their respective territories and shall encourage conditions for the promotion of that identity.

UN Declaration on the Rights of Minorities

Minorities have not been definitively defined by international human rights instruments, but they are commonly described in such instruments as those with national or ethnic, religious or linguistic characteristics that differ from the majority population and which they wish to maintain. These are protected:

- at the UN level by article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as well as by the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities adopted in 1992

- at the European level by a binding instrument – the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM), which created a monitoring body of independent experts: the Advisory Committee on the FCNM. Other Council of Europe sectors have activities relevant to the protection of minorities: the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, the European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), and the Commissioner for Human Rights, amongst others, are instrumental in this.

- by having a special place in the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) by the High Commissioner on National Minorities, and by relevant OSCE documents.

Children

A child means every human being below the age of eighteen years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier.

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

Their main protection is given at the UN level with the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) of 1989, the most widely ratified convention (not ratified only by the United States). The Convention's four core principles are: non-discrimination; a commitment to upholding the best interests of the child; the right to life, survival and development; and respect for the views of the child.

At the African level, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child provides basic children's rights, taking into account the unique factors of the continent's situation. It came into force in 1999. The Covenant of the Rights of the Child in Islam was adopted by the Organisation of Islamic Conference in 2005. The ASEAN Commission on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Women and Children was inaugurated in April 2010.

The Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse came into force on 1 July 2010. This Convention is the first instrument to establish the various forms of sexual abuse of children as criminal offences, including such abuse committed in the home or family.

Refugees

The rights of refugees are specially guaranteed in the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees of 1951 and by the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR). The only regional system with a specific instrument on refugee protection has been Africa with the adoption, in 1969, of the Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, but in Europe the ECHR also offers some protection.

Women

In order to promote worldwide equality between the sexes, the rights of women are specifically protected by the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), 1979.

In the Council of Europe, 2009 saw the adoption of the Declaration: Making Gender Equality a Reality. The adoption of this Declaration marked 20 years after the adoption of another Declaration on the equality of Women and Men. The aim of the 2009 Declaration is to bridge the gap between the equality of genders in fact, as well as in law. It calls on Member States to eliminate structural causes of power imbalances between women and men, ensure economic independence and empowerment of women, address the need to eliminate established stereotypes, eradicate violations of the dignity and human rights of women through effective action to prevent and combat gender-based violence, and the integration of a gender equality perspective in governance.

Others

Groups such as people with disabilities are also given special protection because of their vulnerable position, which can make them more prone to abuse. This is established in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which will be discussed further in Chapter 5.

Other groups too, for example indigenous peoples, have also received specific protection at the international level through the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, although not yet as a legally binding instrument.

Question: Are there other groups in your society that are in need of special protection?

Regional instruments

As we can see above, international and regional instruments generally uphold the same minimum standards but they may differ in their focus or in raising regionally focused concerns. For example, the concern with internally displaced persons was spearheaded in the African region before the issue really emerged as a matter for UN concern; similarly, the mechanism of visiting places of detention in an effort to prevent torture was first established at the European level before an Optional Protocol allowed for the same mechanism under the UN Convention Against Torture. These examples show how regional and international norms and mechanisms can enhance the promotion and protection of human rights.

The practical advantage of having regional human rights norms and systems for the protection of human rights is that they are more likely to have been crafted in the basis of closer geographic, historical, political, cultural and social affinities. They are closer to ‘home' and are more likely to enjoy greater support. They are also more accessible to policy makers, politicians and victims. We may therefore see them as the second ‘front' for the upholding of human rights, the first being domestic, the second regional and the third international.

Four of the five world regions have established human rights systems for the protection of human rights. The objective of regional instruments is to articulate human rights standards and mechanisms at the regional level without downgrading the universality of human rights. As regional systems have developed, whether due to an economic impetus or for more historical or political reasons, they have also felt the urge to articulate a regional human rights commitment, often reinforcing the mechanisms and guarantees of the UN system. Indeed there have been many examples where regional standards exceed internationally agreed standards, one example being the African system's pioneering recognition of the need for protection, not only for refugees but also for internally displaced persons.

Regional human rights standards often exceed UN standards and reinforce them

In the Americas, there is the Organization of American States, and the main binding document is the American Convention on Human Rights of 1969.

In Africa, we find the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, adopted in 1986 within the African Union (formerly known as the Organisation of African Unity).

On the Asian continent, no real system has been developed to date and the only regional human rights instrument is a non-binding 1998 peoples' charter initiated by civil society – the Asian Declaration on Human Rights.

European instruments

Europe has a well-established system within the Council of Europe for the protection of human rights of which the cornerstone is the European Convention on Human Rights with its European Court of Human Rights based in Strasbourg.

Question: Why do you think different regions have found it necessary to establish their own human rights systems?

The Council of Europe, with its 47 member states, has played a key role in the promotion of human rights in Europe. Its main human rights instrument is the European Convention on the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (also known as the European Convention on Human Rights-ECHR). This has been accepted by all the member states in the Council of Europe, since it is a requirement for membership. It was adopted in 1950 and came into force three years later. It provides for civil and political rights and its main strength is its implementation machinery, the European Court of Human Rights. This court and its jurisprudence are admired throughout the world and are often referred to by the UN and by constitutional courts of numerous countries and other regional systems.

Just as at the UN level, social and economic rights in Europe are provided for in a separate document. The (Revised) European Social Charter is a binding document that covers rights to safeguard people's standard of living in Europe. The charter has been signed by 45 member states and, by 2010, it had been ratified by 30 of them.

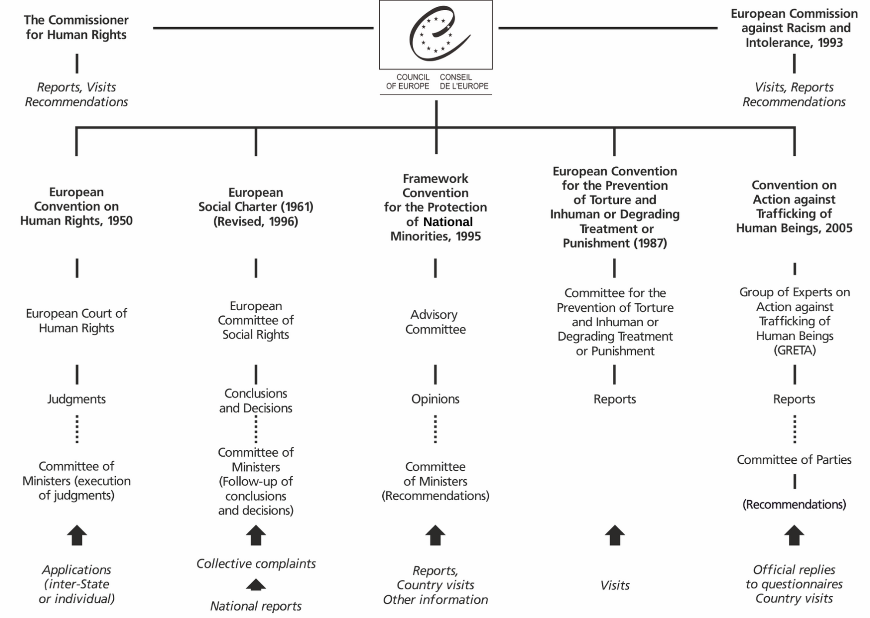

In addition to these two major instruments, the Council of Europe's action in the field of human rights include other specific instruments and conventions that complement the guarantees and provisions of the ECHR by addressing specific situations or vulnerable groups. Conventional monitoring systems are complemented by other independent bodies such as the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance and the Commissioner for Human Rights. Altogether, the work of the Council of Europe for human rights should be able to take into account social, scientific and technological developments, and the possible new challenges that they present for human rights.

Human Rights Development

Human rights instruments are a record of our latest understandings of what human dignity requires. Such instruments are likely to be always one step behind, in that they are addressing challenges that have already been acknowledged rather than those that remain so institutionalised and embedded in our societies that we still fail to acknowledge them as rights and rights violations.

In the Council of Europe, the standard-setting work of the organisation seeks to propose new legal standards to respond to social measures to deal with problems arising in the member States concerning issues within their competence to the Committee of Ministers. These measures may include proposing new legal standards or adapting existing ones. This is how the procedures of the European Court of Human Rights are evolving so that it remains effective, how provisions for abolishing the death penalty have been adopted, and how new convention-based instruments, such as the Convention on Action against Trafficking of Human Beings, adopted in 2005, have come to light.

In this sense, human rights instruments will continue to be revised and advanced for time immemorial. Our understanding, case law and – most of all – our advocacy will continue to push, pull and stretch human rights continuously. The fact that the provisions of human rights conventions and treaties are sometimes seen as being below what we would sometimes expect should not be a reason to question what human rights represent as hope for humanity. Human rights law will often remain behind what human rights advocates would expect, but it also remains their most reliable support.

Main human rights instruments and implementation mechanisms of the Council of Europe

Fighting racism and intolerance

All human rights instruments contain non-discrimination and equality guarantees, whether they are UN, Council of Europe, EU or OSCE standards. At the UN level, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination came into force in 1969 and is monitored by an expert body, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The Committee receives and reviews state reports regarding compliance with the treaty, has an early warning procedure aimed at preventing situations fuelled by intolerance that may escalate into conflict and serious violations of the Convention, and a procedure for receiving individual complaints where the state concerned has allowed for this. The European Union's Race Directive, in turn, applies to employment and to the provision of goods and services by the State and private actors.

The European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) is a mechanism of the Council of Europe. Established in 1993, ECRI's task is to combat racism, xenophobia, anti-semitism and intolerance at the level of Europe as a whole and from the perspective of the protection of human rights. ECRI's action covers all necessary measures to combat violence, discrimination and prejudice faced by persons or groups of persons, notably on grounds of race, colour, language, religion, nationality and national or ethnic origin.

ECRI's members are designated by their governments on the basis of their in-depth knowledge in the field of combating intolerance. They are nominated in their personal capacity and act as independent members.

ECRI's main programme of activities comprises:

- a country-by-country approach consisting of carrying out in-depth analyses of the situation in each of the member countries in order to develop specific, concrete proposals, matched by follow-up

- work on general themes (the collection and circulation of examples of good practice on specific subjects to illustrate ECRI's recommendations, and the adoption of general policy recommendations)

- activities in liaison with the community, including awareness-raising and information sessions in the member states, co-ordination with national and local NGOs, communicating an anti-racist message and producing educational material.

Protocol 12 of the European Convention on Human Rights

An additional protocol to the ECHR was adopted in 2000 and entered into force in 2005; this was Protocol 12. As of early 2011 it has been signed by 19 states and ratified by 18. Its main focus is the prohibition of discrimination.

The ECHR already guarantees the right not to be discriminated against (Article 14) but this is thought to be inadequate in comparison with those provisions of other international instruments such as the UDHR and the ICCPR. The main reason is that article 14, unlike the others, does not contain an independent prohibition of discrimination; that is, it prohibits discrimination only with regard to the "enjoyment of the rights and freedoms" set forth in the Convention. When this protocol came into force, the prohibition of discrimination gained an ‘independent life' from other provisions of the ECHR. The Court found a violation of this provision for the first time in 2009 in Sejdić and Finci v. Bosnia and Herzegovina (GC, nos. 27996/06 and 34836/06, 22 December 2009).

Enforcing human rights

How can we ensure that these protection mechanisms work? Who or what compels states to carry out their obligations?

At a national level, this work is carried out by courts – when human rights instruments have been ratified or incorporated into national law – but also, depending on the country, by ombudsman offices, human rights committees, human rights councils, parliamentary committees, and so on.

The main international supervisory bodies are commissions or committees and courts, all of which are composed of independent members – experts or judges – and none of whom represent a single state. The main mechanisms used by these bodies are:

- Complaints (brought by individuals, groups or states)

- Court cases

- Reporting procedures.

Since not all human rights instruments or regional systems use the same procedures for implementing human rights, a few examples will help to clarify.

Complaints

Complaints against a state are brought before a commission or committee in what is usually referred to as a quasi-judicial procedure. The supervisory body then takes a decision and states are expected to comply with it, though no legal enforcement procedure exists. Often a state needs to give an additional declaration or ratification of an optional protocol to signify its acceptance of the complaints system. The Human Rights Committee (or "ICCPR Committee") and the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (within the United Nations system), and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (within the Organisation of American States) are examples of bodies dealing with such complaints.

Question: What sanctions could exist if we established an International Human Rights Court?

Court cases

European Court of Human Rights

Inter-American Court of Human Rights

African Court on Human and People's Rights

So far there are three permanent regional courts which exist as supervisory bodies specifically for the implementation of human rights: the European Court of Human Rights, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (ACJHR). The Inter-American Court of Human Rights was established by the Organization of American States in 1979 to interpret and enforce the American Convention on Human Rights. The African Court is the most recent of the regional courts, having come into being in January 2004. It decides cases in compliance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights in relation to state members of the African Union. Based in Arusha, Tanzania, the Court's judges were elected in 2006 and it delivered its first judgment in December 2009, declaring it had no jurisdiction to hear the case Yogogombaye v Senegal.

International Criminal Court

After ratification of the Rome Statute by 60 countries, the first permanent international criminal court came into force in 2002 to try cases related to war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. This International Criminal Court (ICC) tries individuals accused of crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes but only if national courts are unwilling or unable to investigate or prosecute these crimes. To date the ICC has investigated five situations in Northern Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic, Sudan (Darfur) and Kenya. Its groundbreaking case law has helped advance human rights understandings, for example in relation to the incitement of genocide and the right to free and fair elections.

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is the principal judicial organ of the UN. It has a dual role: to settle in accordance with international law the legal disputes submitted to it by states, and to give advisory opinions on legal questions. Only states can bring a case against another state and usually the cases are to do with treaties between states. These treaties may concern basic relations between states, (for example commercial or territorial) or may relate to human rights issues. The ICJ does not allow individuals to bring human rights or other claims to it. It has, however, contributed to furthering human rights by interpreting and developing human rights rules and principles in cases which states or international bodies have brought to it. It has addressed rights such as self-determination, non-discrimination, freedom of movement, the prohibition of torture, and so on.

There is often confusion surrounding the roles of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ). In actual fact, the three bodies are very different in terms of their geographical jurisdiction and the types of cases they examine.

The ECJ is a body of the European Union. This is a court whose main duty is to ensure that Community law is not interpreted and applied differently in each member state. It is based on Community law and not human rights law; but sometimes Community law may involve human rights issues.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is the principle judicial organ of the United Nations and its role was discussed above.

The European Court of Human Rights

There were 1,625 judgements delivered by the Court in 2009, which means more than 4 per day (including weekends and holidays!).

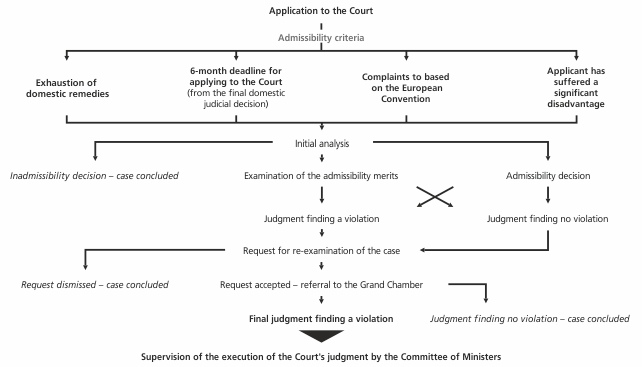

The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg is famous for a number of reasons, but perhaps above all, because it gives life and meaning to the text of the ECHR. One of its main advantages is the system of compulsory jurisdiction, which means that as soon as a state ratifies or accedes to the ECHR, it automatically puts itself under the jurisdiction of the European Court. A human rights case can be brought against the State Party from the moment of ratification.

Another reason for its success is the force of the Court's judgment. States have to comply with the final judgment. Their compliance is supervised by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe.

In every case brought before the European Court, the procedure also includes the possibility of having a friendly settlement based on mediation between the parties. The Court has been able to develop over time. When it was initially set up in 1959, it was only a part-time court working together with the European Commission of Human Rights. With the increase of cases, a full-time court became necessary and one was set up in November 1998. This increase in the number of cases is clear evidence of the Court's success, but this workload is also jeopardising the quality and effectiveness of the system. People know that the Court is there and able to step in when they feel their fundamental rights are being infringed; however, the authority and effectiveness of the ECHR at the national level should be ensured, in accordance with the "principle of subsidiarity", which foresees that states have primary responsibility to prevent human rights violations and to remedy them when they occur.

Proceedings before the European Court of Human Rights

Source: www.echr.coe.int

Some emblematic cases of the European Court of Human Rights

- Soering v. the UK (June 1989): This was a case involving a man who was to be extradited to US to face charges of murder, where the crime was punishable by the death penalty. The Court took the view that to send him back to the US would be against the prohibition of torture, inhuman or other degrading treatment or punishment (Article 3, ECHR). One consequence of this decision was that the protection of individuals within a member state of the Council of Europe went beyond European borders. This principle has already been followed in other cases, such as Jabari v. Turkey (July 2000), and has protected asylum seekers from being sent back to a country where they would have their lives endangered.

- Tyrer v. the UK (March 1978): In this case, the Court considered that corporal punishment as a punishment for juvenile offenders was against the ECHR because it violated the right not to be tortured or to have degrading and inhuman treatment or punishment, as guaranteed under Article 3. In the Court's words: "his punishment – whereby he was treated as an object in the power of the authorities – constituted an assault on precisely that which it is one of the main purposes of Article 3 (Art. 3) to protect, namely a person's dignity and physical integrity". This case is a good example of the living nature of the ECHR, where the Court keeps pace with the changing values of our society.

- Kokkinakis v. Greece (April 1993): This was an interesting case, which dealt with the conflict between the rights of different people. It was based on the issue of proselytising and whether the teaching of a religion (guaranteed under article 9 of ECHR) violates another person's right to freedom of religion. The court thought it necessary to make a clear distinction between teaching, preaching or discussing with immoral and deceitful means to convince a person to change his/her religion (such as offering material or social advantages, using violence or brainwashing).

- DH v Czech Republic (November 2007): This was a case taken by 18 Roma children in the light of the fact that Roma students were segregated into special schools for children with learning disabilities, regardless of their ability. This meant that they would also have little chance in subsequently accessing higher education or job opportunities. In its judgment, the Court for the first time found a violation of article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) in relation to a "pattern" of racial discrimination in a particular sphere of public life, in this case public schools. The Court ruled that this systemic pattern of racial segregation in schooling violated non-discrimination protections in the ECHR (Article 14). It also noted that a general policy or measure, couched in neutral terms, may still discriminate against a particular group and result in indirect discrimination against them. The case was a first in challenging systemic racial segregation in education.

Question: Do you know of any important cases against your country at the European Court of Human Rights?

Reports and reviews

The majority of human rights instruments require states to submit periodic reports. These are compiled by states following the directions of the supervisory body. The objective of such reporting, and the subsequent review with the corresponding monitoring body, is a frank exchange of challenges being faced in efforts towards the realisation of the rights concerned. The reports are publicly examined in what is referred to as the ‘state dialogue'. The state reports are examined alongside any NGO ‘shadow reports', based on their own sources and analysis, addressing the record of that state. After the dialogue between state representatives and independent expert members of the monitoring body, that body issues its observations regarding the compliance of that state with the standards upheld in the binding instrument under review. These observations address both positive and critical aspects regarding the state's record. The ICCPR, ICESCR, and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) are examples of instruments requiring the submission of such periodic reports.

As well as this state dialogue procedure, monitoring bodies may also be empowered to carry out ‘in situ' or field visits to observe the situation of human rights first hand. Most such visits require the explicit permission of the state on a case-by-case basis. However, efforts are being made to allow for open standing invitations, for example with states publicly issuing standing invitations for visits by any UN Special Mandate holders.

More robust procedures have also been developed under a number of instruments to allow for intrusive ongoing visits, in the effort not only to respond to, but also to prevent, violations of human rights.

The CPT Prevents ill-treatment of persons deprived of their liberty in Europe

The European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1987) offers one such example. It is based on a system of visits by members of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) to places of detention, for example prisons and places of youth detention, police stations, army barracks and psychiatric hospitals. Members of the CPT observe how detainees are treated and, if necessary, recommend improvements in order to comply with the right not to be tortured or to be inhumanly treated. This mechanism has since inspired the development of a similar UN mechanism. CPT delegations periodically visit states that are party to the Convention but may organise additional ad hoc visits if necessary. As of 9 August 2012, the CPT had conducted 323 visits, and published 272 reports.

The reports of the CPT are usually public: http://www.cpt.coe.int

An important function of the CPT's work was seen in the case of the hunger strikes in Turkish prisons in 2000-2001. When the Turkish government was drawing up changes to the prison system, a number of prisoners used hunger strikes to protest against some of the reforms. Their demonstrations became violent. The CPT became actively involved in negotiations with government and hunger strikers, investigating the events surrounding the hunger strikes and looking at how the draft laws could reform the Turkish prison system. The CPT has visited Turkey every year since 1999, except in 2008. More recent CPT visits have included those to Serbia, Albania and Greece.

The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights

The office of the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights was set up in 1999. The purpose of this independent institution is both to promote the concept of human rights and to ensure effective respect for and full enjoyment of these rights in Council of Europe member States. The Commissioner is elected by the Parliamentary Assembly for a non-renewable term of office of six years.

The Commissioner is a non-judicial institution whose action is to be seen as complementary to the other institutions of the Council of Europe which are active in the promotion of human rights. The Commissioner is to carry out its responsibilities with complete independence and impartiality, while respecting the competence of the various supervisory bodies set up under the European Convention on Human Rights or under other Council of Europe human rights instruments.

The Commissioner for Human Rights is mandated to:

- foster the effective observance of human rights, and assist member states in the implementation of Council of Europe human rights standards

- promote education in and awareness of human rights in Council of Europe member states

- identify possible shortcomings in the law and practice concerning human rights

- facilitate the activities of national ombudsperson institutions and other human rights structures, and

- provide advice and information regarding the protection of human rights across the region.

The Commissioner can deal ex officio with any issue within its competence. Although it may not take up individual complaints, the Commissioner can act on any relevant information concerning general aspects of the protection of human rights as enshrined in Council of Europe instruments.

Such information and requests to deal with it may be addressed to the Commissioner by governments, national parliaments, national ombudsmen or similar institutions, as well as by individuals and organisations. The Commissioner's thematic work has included the issuing of reports, recommendations, opinions and viewpoints on the human rights of asylum seekers, immigrants and Roma.

The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights should not be confused with the United Nations Human Rights Commissioner for human rights.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

Many NGOs lobbied for the creation of the post of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the decision for its creation was agreed at the UN World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna in 1993, which recommended that the General Assembly consider the question of establishing such a High Commissioner for the promotion and protection of all human rights as a matter of priority. This was done in the same year.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights is appointed by the UN Secretary-General and approved by the General Assembly as a "person of high moral standing" with expertise in human rights as the UN official with principal responsibility for UN human rights activities: their role includes the promotion, protection and effectively enjoyment of all rights, engagement and dialogue with governments on securing human rights, and enhancing international co-operation and UN co-ordination for the promotion and protection of all human rights. As the principal human rights official of the UN, the High Commissioner's activities include the direction of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and its regional and country offices. The OHCHR supports the work of a wide range of UN human rights activities and works for the promotion and protection of human rights and the enforcement of universal human rights norms, including the World Programme on Human Rights Education.

Is this sufficient?

Many people would argue that the poor human rights record in the world is a result of the lack of proper enforcement mechanisms. It is often left up to individual states to decide whether they carry out recommendations. In many cases, whether an individual or group right will in fact be guaranteed depends on pressure from the international community and, to a large extent, on the work of NGOs. This is a less than satisfactory state of affairs, since it can be a long wait before a human rights violation is actually addressed by the UN or the Council of Europe.

Can anything be done to change this? Firstly, it is essential to ensure that states guarantee human rights at national level and that they develop a proper mechanism for remedying any violation. At the same time, pressure must be put on states to commit themselves to those mechanisms that have enforcement procedures.

Notes

2 http://www.un.org/en/globalissues/briefingpapers/humanrights/quotes.shtml

- Chapter 1 - Human Rights Education and Compass: an introduction

- Chapter 2 - Practical Activities and Methods for Human Rights Education

- Chapter 3 - Taking Action for Human Rights

- Chapter 4 - Understanding Human Rights

- Chapter 5 - Background Information on Global Human Rights Themes

- Appendices

- Glossary

Human rights protections are ultimately most reliant on mechanisms at the national level