Playground design was revolutionized several times throughout the 20th century. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, published their grand project Century of the Child: Growing by Design, 1900-2000, in 2012, representing a large scale effort to investigate intersections of children and design. It describes how the exuberant reappearance of children in public urban space engaged in unregulated play in the rubbles of WWII evoked architects and designers to rethink children’s playgrounds - e.g. Van Eyck, Aldo; Sorensen, Carl[1]. Two decades later, in 1970, several pioneering professional publications focused entirely on playground design - e.g. Dattner, Richard; Friedberg, Paul; Hurtwood, Lady Allen[2]. They proposed innovative, imaginative, challenging and educational orientated play-spaces, designed to provide play opportunities for all age groups, genders and also accommodate interplay (play between different age groups, e.g. grandparents with grandchildren).

However city population and demographics have changed significantly since the 1970’s, especially in Europe’s largest and/or capital cities. “The free movement of EU nationals within the Union, unrest in a number of neighbouring countries around the EU, migrant flows and asylum seekers are just some of the many reasons why cities in the EU have become more culturally and ethnically diverse. Indeed, most EU cities have seen their share of non-nationals grow in recent decades“[3]. This new urban social environment challenges designers to reconsider playground design, especially in intercultural cities.

Jerusalem could be considered an extreme case study of an intercultural city. Two thirds of the city’s population of 820,000 are Jews, 1st, 2nd or 3rd generations of immigrants from literally the entire world. One half of these Jews are Ultra-Orthodox with large families (5.5 children per family), the other half secular (2.2 children per family), with extreme tensions between them. The last third of the population of Jerusalem are Arabs (4.8 children per family). The Christian minority is very small. This mosaic Jewish demography coupled with the political tensions between the Jews and the Arabs (Palestinians), the high birth rates and lack of job opportunities - create extraordinary challenges for the city in general – e.g. social, economic, education, health, labour, security.

During the construction booms of the 80’s and 90’s decades, standard “play kits” were installed in most Jerusalem neighborhoods. When visiting nowadays these playgrounds within the neighbourhoods of the Ultra-Orthodox and to the Moslem Arabs, it is surprising to see how empty they are. The children (under the surveillance of their mothers and/or grandmothers), teenagers and young adults are playing outside, on the streets or in public gardens (if available), however not in these dedicated playgrounds. The Municipality of Jerusalem therefore decided in 2015 to challenge the students of the Masters of Urban Design Program in the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem to create innovative design solutions. Three groups of students deliberately took the challenge to design innovative playgrounds for the Ultra-Orthodox Jews and the Muslim Arabs.

From the perspective of urban playground design, the demographic factor of high children rate from low income families (small apartments/less home entertainment), results in the acute need for vast quantities of outdoor playgrounds and recreational spaces. The designer must consider unique climate and topography issues (Jerusalem is spread out over seven hills). However, in addition to the above obvious issues, the urban designer in Jerusalem must also overcome the specific cultural restrictions imposed on and by Ultra-Orthodox Jews and Muslim Arabs, to mention a few:

- Play-space Location Issues – Muslim Arab towns and villages traditionally do not allocate land for public space. Even if empty land is detected, leased and provided for a playground, the outcome could be totally unexpected according to Western standards - e.g. used for waste disposal; used at night exclusively for gatherings of loud young men that disturb the nearby neighbours.

- Player Gender Issues – Neither Orthodox Jew nor Muslim teenage girls and boys are allowed to play together.

- Women mobility issues – Both single and married Ultra-Orthodox Jewish women as well as Muslim Arab women or mothers could have restrictions as to where, when and how they can go outside their domestic dwelling areas.

- Cultural issues – certain play can cause violations of dress or dignity codes, e.g. outdoor physical exercise installations; certain sports; dancing.

- Vandalism issues - playground vandalism can occur as a means of social or political protest (the author prefers not to elaborate on this issue since this is a design and not a political article).

These heritage factors make public outdoor playground design in Jerusalem for the Ultra-Orthodox Jews and the Muslim Arab neighbourhoods an incredible challenge for play, and more so for interplay. On the upside, they also present an incredible opportunity - to create a unique playground, cherished by the community and interesting for visitors.

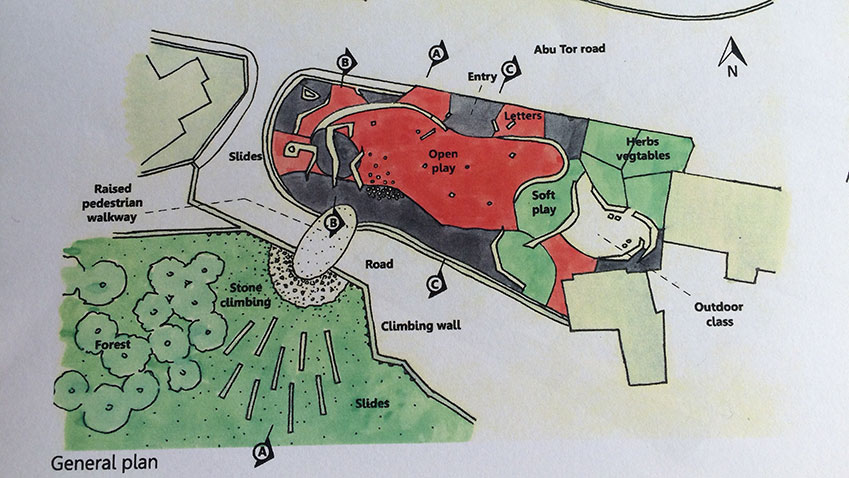

The author of this article from Ottawa co-designed together with fellow colleague Architect Matti Rosenshine from Chicago, a new playground for the Muslim Arab neighbourhood of Abu Thor, East Jerusalem, featured in the images. The site ‘Naomi” playground previously featured a small plastic “kit” installation - a climb ladder, crawl through barrel, and slide – that was burnt down by the locals the year before out of protest.

A participatory heritage mapping was carried out before starting the design process. Males and females from all ages in Abu Thor, including the elderly, were interviewed to map various parameters, to mention a few: circulation patterns and walking distances of the players to playgrounds within their neighbourhood and the surrounding city; their play and interplay types, times, habits, preferences and wishes; cultural, gender and age play issues; their sense of identity and inclusion in their local ‘Naomi’ playground and in hosting surrounding playgrounds.

After analysing the heritage mapping, principles of design were chosen with the goal to provide the community with a unique, exclusive and sustainable playground they will identify with and be proud of. A short list of principles:

- adopt design elements from the Muslim Arab culture – e.g. Islam calligraphy, traditional gardening and flooring.

- use local familiar materials – e.g. olive tree wood and local stone (both resistant to vandalism)

- entice community play and interplay for all ages/genders – e.g. using partitions and screening between play zones

- utilize the space during the entire day – e.g. outdoor classroom zone, infant zone, elderly zone (table games)

- enlarge the playground to accommodate for the 7,000 children and create a “feel risky/play safe” zone – e.g. connect the small playground to the nearby large forest, and design long slides down the steep slope and rock climbing to get back up

- have the local community participate in the actual preparation and assembly of the playground (the Palestinians are skilled builders) as a means for additional participation, a preventive for future vandalism, and taking ownership.

The design process included public participation from all ages, and was fine-tuned accordingly. In February 2016, the village Mukhtar (Chief) and other delegates from the village attended the final presentation, along with officials from the Jerusalem Municipality and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. At the end of our presentation, the village Mukhtar stood up and expressed the wish of the village to execute the proposed project. The authorities approved, and the project is now underway. The participatory heritage mapping was key to the success of this endeavour.

Still early to confirm, there is room for optimism that the local Arab population will identify and take ownership of their new public play-space, and proudly host their neighbouring Jewish and Christian guests and/or tourists from around the world (Abu Thor is a 5 minute walk from the ancient city of Jerusalem).

With the growing number of immigrants into the cities of Europe, this case study could be relevant for rethinking playground design in intercultural cities. Urban Play is important not only for the development of the child who later becomes the adult, but also as a means to create interaction and engagement between the residents and communities of the city, that could activate the city socially, removing tensions, enticing integration and creating a friendlier and more enjoyable city for all.[4]

[1] Aldo van Eyck hundreds of playgrounds designed with derelict “in-between spaces” in Amsterdam; Carl Sorensen’s experimental “junk” playground in Copenhagen.

[2] Design for Play by Richard Dattner; Play and Interplay by Paul Friedberg; Planning for Play by Lady Allen from Hurtwood

[3] Eurostat, Statistics on European Cities, data extracted in March 2015

[4] See article “Urban Play as a Means for Activating Intercultural Cities”, by Rennen Zunder, Urban Designer, published November at the CoE International cities programme Newsroom.